Visualizing the Civil Rights Movement: Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, AL

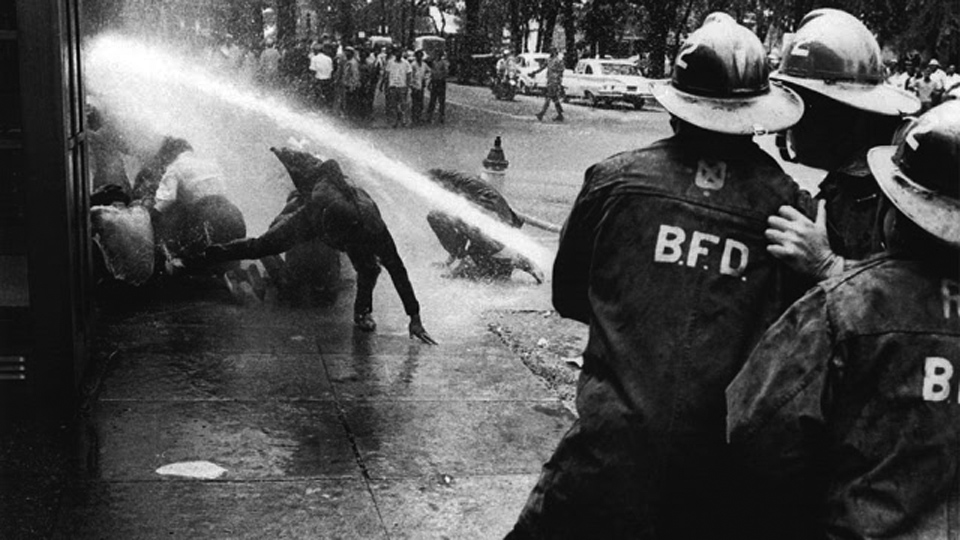

/In 1963, student protesters took to the streets of Birmingham, AL in protests captured in iconic photographs that shocked the nation. Fire hoses and dogs were used by police against children and many were arrested in the efforts to desegregate the city. Located just across the street from the 16th Street Baptist Church, Kelly Ingram Park served as a central location for the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham. Today the park is part of the city’s efforts to remember the Civil Rights Movement of Birmingham. The 16th Street Baptist Church, site of the infamous 1963 bombing, and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute are located right across the street and there are interpretive signs through the city following the routes of several marches that happened in the 1960s.

The park features several monuments commemorating the Civil Rights Movement. Towards the center of the park stands a traditional monument to Martin Luther King, Jr, whose work in Birmingham is best known through his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” There is also a statue to Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, a hero of the Birmingham movement, outside of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. These two traditional statues honor important leaders to the movement, however many of the monuments in Kelly Ingram Park focus on the student protests that captured the attention of the whole country.

The “Foot Soldier” monument designed by Ronald McDowell recreates the infamous photograph of a police officer grabbing a young man by the shirt while the police dog aggressively lunges forward. This iconic image is used to honor those who marched and demanded equality in Birmingham.

On the next corner over is a moving tribute, titled Four Spirits, to the four girls who were killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 16, 1963. Located on the corner closest to the church, the four girls are represented around a bench: Cynthia Wesley sits on one end of the bench with a Bible in her lap. Carol Denise McNair, the youngest girl killed, releases doves into the air while Addie Mae Collins ties a sash around her dress. The fourth girl, Carole Robertson, stands apart from the bench, in motion as she beckons the girls to church. This sculpture was done by Elizabeth MacQueen and unveiled in 2013 for the 50th anniversary of the bombing. The sculpture is a beautiful tribute to the innocence of the victims, with the release of the doves symbolizing the hope for peace or the release of these four spirits to heaven. Particularly moving to me, there is a pair of shoes on the ground by the bench under McNair and Collins. Both figures are barefoot in the sculpture, so it is not clear whose shoes they are. However, the shoes that McNair was wearing when she was killed are on display at the Civil Rights Institute, along with other personal effects she had on her that day and the piece of shrapnel found in her skull. As a new mom, that display hit me hard (I am not ashamed to say I cried a bit) and so the detail of the shoes in the sculpture was another layer of meaning, another connection to the humanness of this story.

Kelly Ingram Park evoked a lot of emotion as I walked through. There are three installations by James Drake along a circular path called the “Freedom Walk.” These art pieces capture well known events and photographs in metal sculptures that evoke a deep connection to the experiences of the children involved in the march. One sculpture shows two children bracing themselves against a wall while two water cannons stand a few feet from the main sculpture, aiming at them. The second sculpture represents the children who were arrested and jailed for their role in the protests. On one side of the path two children stand framed in metal with the words “I ain’t afraid of your jail” in large letters across the bottom. On the other side of the path another metal frame is fitted with bars. If you stand in the grass in front of the sculpture it appears that the two children are in jail. The third installation is two metal walls, one on either side of the path, with metal dogs leaping out into the space occupied by the path.

I’ve always been interested in monuments. I love photographing them and learning about their design and intended meaning. These installations at Kelly Ingram park are different than most of the monuments I’ve looked at. They bring you into the scene and evoke a deep, gut-felt reaction. In each of the installations the path takes you straight through in sculpture. In the first, you stand at the wall facing the water cannons. In the second, as you walk through it is as if you are entering the jail cell with the two children. The third is the most intense; the path takes you through the dogs and you weave through them to get to the other side. I must admit, I could not walk through it. It was so intimidating that I ended up walking around. This was the first time I ever had that reaction to a sculpture or monument; the impact of the piece was amazing.

Besides commemorating the events of the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham and the lives lost there, the installations at Kelly Ingram Park bring the visitor into the events. They make the viewer part of the action, a reminder of the intense human emotion and struggle that marked the movement. By emphasizing the human toll—through the Four Spirits and “Foot Soldier” monuments—the park creates a connection between present and past for the viewer (you can connect on that human level with those represented in the monuments). By forcing the visitor into the sculptures themselves with the other installations, it really asks the viewer to step into the shoes of the protesters, consider what challenges they faced in their quest for equality, and question whether they could have stood the test. The monuments in the park stir emotion and create a message stronger than a lot of monuments. If you are ever in Birmingham, I hope you stop by the park and walk through (and visit the Civil Rights Institute as well).

Dr. Kathleen Logothetis Thompson earned her PhD in Nineteenth Century/Civil War America from West Virginia University, and also holds a M.A. from WVU and a B.A. from Siena College. Her research is on mental trauma and coping among Union soldiers and she is currently working on her first book, tentatively titled War on the Mind. She currently teaches history at several colleges and universities and leads tours of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. Kathleen was a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park for several years and is the co-editor of Civil Discourse.