The Invisible Toll: Mental Trauma and 'Total War'

/From a paper presented at the Filson Institute Conference in 2014.

Total War is usually defined as unrestricted warfare, particularly in terms of mobilization, objectives, and people involved. A type of warfare connected to the modern age, this strategy is often known for more intense combat or the involvement of civilians, particularly in a society’s mobilization of resources to support the war effort. A society waging total war uses all of its resources in that effort and often targets the entirety of their enemy’s resources as well. While total war is definitively seen in the conflicts of the twentieth century, scholars have debated whether this strategy was used during the Civil War. While some historians and enthusiasts point to campaigns such as Sherman’s “March to the Sea” as examples of total war, scholars including Mark Neely and Mark Grimsley argue that warfare in the Civil War never escalated to unrestricted, total warfare.

Instead of delving into that exact debate, this piece uses the concept of total war in a more abstract sense. Central to the concept of total war is the full mobilization of resources and a more intense experience of warfare. While the technologies and material goods of warfare have changed drastically over time, the most basic resource of warfare has changed very little—the men (and now women) who fight. Historians and psychologists who study combat stress reactions argue that the physical and psychiatric reactions to trauma have not changed over the course of history, although our knowledge and understanding of these reactions have. As historian Richard Gabriel states, “It is important to understand the historical record of combat breakdown for the simple reason that while the technology of war has changed considerably over the centuries, the raw material of war—the men who must fight it—has changed little or not at all. Technology…will mean nothing if men cannot withstand the storm of battle.” Men must withstand battle and the full experience of soldiering in a physical, emotional, and mental sense. War is of course physical, but it is also a psychological struggle in which men seek to maintain their own mental health while weakening that of their enemy in order to convince them to retreat or ultimately surrender. “War means forcing one’s own will on others by physical means,” argues Elmar Dinter. “Its purpose, however, is not the killing of the enemy. He has to be made to believe that he is weaker and, later, that he is defeated, in order to make him surrender. The dead and the injured are only a means to this end. At its core, war is a battle of minds.”

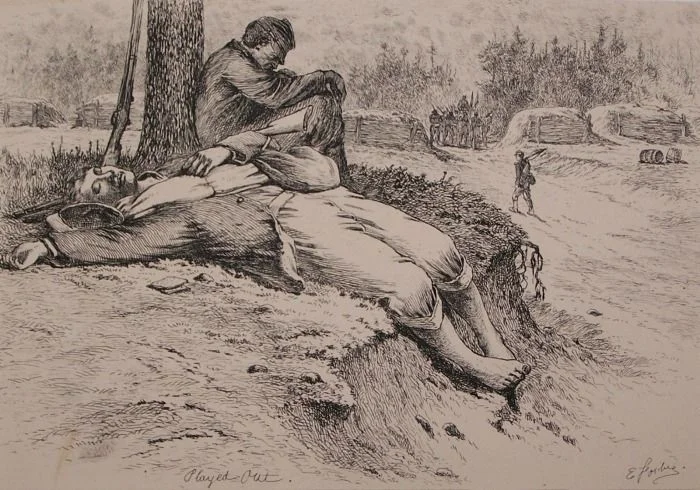

As a battle of minds, warfare is constantly requiring full mobilization of a soldier’s own personal resources, thus reflecting elements of total war within the singular unit of the soldier. When the body reacts to stress, it mobilizes all its energy resources and shuts down nonessential functions in order to focus on survival. When the stressor ends, the body feels weakened as it tries to rebalance itself and return its systems to normal. In a situation where the stressor does not go away, for example in extended combat, the body is held at a heightened state for a longer period of time, exhausting its energy resources and making it harder for it to rebalance itself. Because trauma and stress are different for every individual soldier, each person reacts differently to the situation of combat; however, every soldier is at risk of experiencing trauma and breaking down. Psychologists and historians have used a variety of imagery to convey the limited nature of a soldier’s resources, from a bank account that a soldier constantly withdraws from to a “well of fortitude” that eventually runs dry.

Historian Eric Dean, Jr. reports that one lesson learned from World War II was that “every man has his breaking point,” every man is at risk from environmental stress. Psychiatric staff during that war determined that American troops lost their effectiveness after one hundred days of intermittent exposure to battle, and that breakdown could be expected after about two hundred total days. These totals might not be accurate for the Civil War, but the underlying psychology seems similar. Men broke down after a period of exposure to battle, some more acutely than others. The new style of warfare in the late war period might have accelerated that process.

In order to examine the stress of combat as “total war” on a soldier I will focus on the last years of the war, the period scholars primarily associate with arguments about total war in the Civil War. The psychological process of dealing with combat stress occurred throughout the war, but the style of warfare was changing by 1864 which possibly heightened the rates of soldier breakdown. As examples, I will look at suicide rates in the Union army, the experiences of prisoners of war leading to trauma and suicide, and rates of admission into the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, DC.

In research for my Master’s Thesis, I did statistical and anecdotal analysis of 101 cases of suicide in the Union army. Of the suicide cases I identified, the largest numbers came in 1863 and 1864. Besides a continuation of the issues experienced in 1861 and 1862, warfare was changing. These years saw the introduction of continuous campaigns; unlike the spaced out battles of the early war years, soldiers now fought continually for weeks or months at a time. In these campaigns battles lasted longer, meaning that soldiers spent more time on the same fields faced with the carnage, wounded, and dead of the previous days, and fought increasingly with assaults on entrenched positions. The terrain of some of these battlefields denied the possibility of quick victories and created a confusing and terrifying environment for the men fighting in it. For example, the terrain of the Wilderness in northern Virginia was a terrifying location in which soldiers fought two battles. Fighting in the woods created confusion during the battle, but it also brought the danger of fire which prompted veteran Frank Wilkeson to recount scenes from the Battle of the Wilderness after the war and remember the wounded men, unable to escape from the field. “The bare prospect of fire running through the woods where they lay helpless, unnerved the most courageous of men, and made them call aloud for help,” he wrote. “I saw many wounded soldiers in the Wilderness who hung on to their rifles, and whose intention was clearly stamped on their pallid faces. I saw one man, both of whose legs were broken, lying on the ground with his cocked rifle by his side and his ramrod in his hand, and his eyes set on the front. I knew he meant to kill himself in case of fire—knew it as surely as though I could read his thoughts.” For two days the armies struggled at the Wilderness, resulting in 30,000 casualties. Fires did indeed rage through the woods and claimed the lives of many wounded soldiers who could not get away. A new level of terror was added to battle.

This new mode of warfare was grueling on the soldiers, wearing them down continuously. Where previously soldiers had been able to recuperate between the traumatic experiences of warfare, in 1864 continual campaigns did not allow them the time to rest, physically or emotionally. As Historian Earl J. Hess writes, “Continuous marching, digging entrenchments, skirmishing, repelling or launching frontal assaults, hastily burying the dead, and beginning the cycle of combat all over again was the rule for months.” This left the men exhausted and combat inefficient and drove many to the breaking point. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. said of Grant’s Virginia 1864 campaign that “many a man has gone crazy since this campaign began from the terrible pressure on mind & body.” For men that had enlisted in 1861 or 1862 these continuous campaigns of 1863 and 1864 were coming after years in the field, when the vulnerability created from changes in themselves and their support structure, the weariness of soldiering, and the losses of comrades had already set in.

For Henry Paff of the 77th Illinois Infantry, the 1863 Vicksburg campaign may have led to his breaking point. His regiment was part of the wing of Grant’s force sent to capture Vicksburg while the other wing kept Confederate forces pinned in the northern part of the state. Traveling from December 20, 1862 to December 27, 1862, they were then engaged until January 11, 1863, seeing their first real combat and regimental losses. That winter, in addition to the unsanitary, muddy, and disease-ridden existence in camp, Grant pushed through a series of Bayou Expeditions, all of which failed. Once warmer weather returned the regiment was in constant motion, marching, traveling, performing picket duty, and fighting in battle from April 16, 1863 when they broke camp at Miliken’s Bend to the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. Despite their victory, however, the men were not allowed to rest and they were back on the move the next day. When assigned to guard the wagon train on July 10, the men relished the opportunity for an “easier” duty; however, their major, perhaps seeking some personal glory, ensured his men were transferred back to the front lines the next day. They first held a position just behind the line and then in front of their main line, receiving enemy fire for over twenty-four hours. Sometime during that day, July 11, 1863, Corporal Paff committed suicide. With continual action and no time to recover Paff may have reached his breaking point quickly.

1864 is the year most known for continuous campaigns, the most famous of which are Grant’s Overland Campaign in Virginia and Sherman’s campaign in the south. Both campaigns would push the soldiers hard. “I’m getting tired of this kind of business,” complained Jim Wilson in May, “for nearly three weeks now it has been march and fight all the time.” Beginning in early May 1864, the Overland Campaign saw the Union and Confederate armies fight a continually southern-moving campaign until settling into a ten-month siege around Petersburg, VA in June. Writing in August, James Elliott reported that “on the height of Petersburg we remained there six weeks without being relieved . . . our company is pretty well run down at this time.” The campaign was broken in April 1865 in a series of movements that took the armies to Appomattox. Lorenzo G. Babcock took his life May 6, 1864 near Todd’s Tavern after the first engagement at the Wilderness and a few months later artilleryman Stephen Zoller committed suicide near Weldon Railroad as the armies settled into the siege of Petersburg. Campaigning through Georgia with Sherman, suicide was also the answer for Peter Jacot of the 16th Illinois Cavalry; he killed himself on a battlefield near Atlanta, GA on July 31, 1864. A few months later William Hoerhold did the same; comrades estimated that they had spent forty-two days engaged in the siege of Atlanta and lost one-fifth of the army before taking possession of the city.

Maneuverings away from the battlefield also increased the traumatic nature of the later years of the war, particularly in the experience of prisoners of war. Early in the war prisoners were usually kept only for a few days before being paroled and in July 1862 both sides agreed to a cartel outlining the proper exchange of prisoners. A year later, however, the system collapsed over disputes about how to deal with African-American prisoners. Prisoner exchanges came to a halt and led to extended situations in prisons such as Andersonville, Georgia and Elmira, New York. In the unfortunate circumstances of these camps, prisoners had inadequate shelter, clothing, food, and little stimulation.

The foundations soldiers clutched to manage their wartime experiences completely broke down in the environment of prisoner camps, even breaking the bonds of camaraderie so crucial to surviving camp life and battle. Deprivation, monotony, cruelty, disease, and death forced some prisoners to sink into apathy and face long-standing psychological and physical issues and others to consider or commit suicide. Francis Amasa Walker wrote of his time as a prisoner of war that he suffered “a period of nervous horror such as I had never before and have never since experienced, and memories of which have always made it perfectly clear how one can be driven on, unwilling and vainly resisting, to suicide. I remember watching the bars at my window and wondering whether I should hang myself from them.” Walker resisted such temptation, but others could not, despite the restrictions of available materials in the prison camp. One cavalryman tried to cut his throat with a dull knife and another man used his suspenders as a noose. The “dead line” was an apparently popular form of committing suicide; this was a perimeter set up at many prison camps, either an imaginary line or marked in ways such as the “narrow strip of board nailed on uprights running about the enclosure” described by one Andersonville inmate. This marked the point prisoners could not pass without being shot by the guards. “One step over,” wrote Austin Carr in 1864, “and the penalty is death.” For prisoners with no other means of ending their lives, this was an opportunity to have others do it for them. There are reports of several men purposely stepping over that line, including one whose mission failed when the guard refused to shoot him. There is no question that these men wanted death; one soldier stepped over the line and challenged the sentry to shoot him, after two failed shots he yelled at the guard to do his duty and the third shot hit him in the head, killing him instantly.

For those soldiers who broke down while in the Union army, treatment was not easily accessible. Even though psychiatry was a growing field in the nineteenth century, most Civil War medical personnel did not have much knowledge about mental trauma or treated traumatized soldiers as malingerers. In order to reduce the chances that nostalgia or mental illness would become an easy “out” for soldiers, the army put specific regulations in place regarding the treatment and discharge of soldiers declared insane. The overall policy of the army was to not allow the discharge of soldiers before their enlistment expired, except due to a court-martial sentence or a certificate of disability. The process to receive a certificate of disability was involved and time-consuming. A physical illness or disease was far easier to prove than mental illness or trauma in the Civil War, yet even soldiers who were deemed physically unfit for duty might not be given a certificate of disability; instead soldiers who could still be useful in lighter duties were reassigned to the Invalid Corps, later known as the Veteran Reserve Corps. Only those soldiers suffering from specific deformities, injuries, or ailments were exempt from the Invalid Corps and discharged. As for insane soldiers, the Surgeon-General’s Office specifically stated that insane soldiers could not be discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability.

Instead of receiving a discharge, insane soldiers were supposed to go to the Government Hospital for the Insane (GHI) in Washington D.C., also named St. Elizabeth’s Hospital by sane soldiers recuperating in the military hospital there. While state and local governments ran most mental hospitals in the country, the Government Hospital for the Insane was the first and only federally funded asylum. Founded in 1855, the purpose of the GHI was specifically to treat members of the United States armed forces, with the ability to care for mentally ill residents of the District of Columbia if there was room available. In General Orders No. 98, the Adjutant-General’s Office declared that insane soldiers were entitled to care and set up procedure to send soldiers to the GHI for treatment. From June 1860 to June 1862 the Government Hospital for the Insane admitted 460 men from the Union army; from June 1862 to June 1865 the hospital admitted 993 patients from the army. The hospital’s superintendent did not make a connection between the increasing numbers of admissions and the conditions of war, but it is possible that the later years of the war saw more psychiatric casualties due to the changing nature of warfare.

While these three sets of examples are brief, they suggest that the period known for a more intense style of warfare also saw higher numbers of mental trauma and suicide among Union soldiers. Soldiers throughout the war had to manage their wartime experiences and maintain their physical and mental health; however, the changing nature of warfare in the second half of the Civil War possibly accelerated breakdown and stress reactions in soldiers. With soldiers in a constant state of heightened awareness during continuous campaigns and entrenched warfare or the increasingly worsening situation in prisoner of war camps, the mental experience of soldiering was, in essence, total war upon the soldier, requiring mobilization of all of his physical, emotional, and mental resources in order to survive.

Dr. Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated with her Ph.D. from West Virginia University in 2017. She earned her M.A. from West Virginia University in 2012 and her B.A. in history with a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies from Siena College in 2010. In addition, Kathleen was a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park from 2010-2014 and has worked on various other publications and projects.

Sources:

Benton, Charles E. As Seen From the Ranks: A Boy in the Civil War. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1902.

Black, Jeremy. The Age of Total War, 1860-1945. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006.

Carr, Austin.Ddiary (excerpted transcript), US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA, The Harrisburg Civil War Round Table Collection, Box 7.

Cook, S.G., and Charles E. Benton, ed. The “Dutchess County Regiment” (150th Regiment of New York State Volunteer Infantry) in the Civil War; Its Story as Told by its Members. Danbury, CT: The Danbury Medical Printing Co., Inc., 1907.

Dean, Eric T., Jr. Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and The Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Dinter, Elmar. Hero or Coward: Pressures Facing the Soldier in Battle. Totowa, NJ: Frank Cass and Co., Limited, 1985.

Gabriel, Richard A. No More Heroes: Madness & Psychiatry in War. New York: Hill and Wang, 1987.

Grace, William. The Army Surgeon’s Manual: For the Use of Medical Officers, Cadets, Chaplains, and Hospital Stewards. [Reprinted with a Bibliographical Introduction by Ira M. Rutkow, M .D., Dr. P. H.] San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1992.

Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Towards Southern Civilians, 1861-1865. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Grossman, Dave, Lt. Col. On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (New York: Back Bay Books, 2009.

Hess, Earl J. The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat. Lawrence, KS: The University of Kansas Press, 1997.

Holmes, Richard. Acts of War: The Behavior of Men in Battle. New York: The Free Press, 1985.

Illinois. Military and Naval Department, Jasper N. Reece, and Isaac Hughes Elliott. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois, Volume IV, Containing Reports for the Years 1861-1866. Springfield, IL: Phillips Bros, State Printers, 1901. GoogleBooks.

Lindermann, Gerald F. Embattled Courage: The Experience of Combat in the American Civil War. New York: The Free Press, 1987.

Logothetis, Kathleen Anneliese. “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army.” West Virginia University, M.A. Thesis, 2012.

Lyth, Alfred. “The Andersonville Diary of Private Alfred Lyth.” Niagra frontier 8, no. 1 (1961): 22.

Marvel, William. Andersonville: The Last Depot. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

National Archives: Reports of the Government Hospital for the Insane, Vol. 1, 1855-1874. Office of the Chief Clerk, Department of the Interior. Record Group 48.

Neely, Mark E., Jr. The Civil War and the Limits of Destruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Patten, George, Lt.-Col. Patten’s Army Manual: Containing Instruction for Officers in the Preparation of Rolls, Returns and Accounts Required of Regimental and Company Commanders, and Pertaining to the Subsistence and Quartermasters’ Departments. New York: J. W. Fortune, 1862.

Sanders, Charles W., Jr. While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Shalit, Ben. The Psychology of Conflict and Combat. New York: Praeger, 1988.

SoldierStudies.org.

VanWyck, Richard T. A War to Petrify the Heart: The Civil War Letters of a Duchess County, N.Y. Volunteer. Edited by Virginia Hughes Kaminsky. Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Press, 1997. US Army Heritage and Education Center, PA.

Wilkeson, Frank. Recollections of a Private Solider in the Army of the Potomac. New York and London, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1887.

Winschel, Terrence J. The Civil War Diary of a Common Soldier: William Wiley of the 77th Illinois Infantry. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

Yanni, Carla. The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Case of Lorenzo G. Babcock: Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York For the Year 1903. Registers of the One Hundred and Twenty-first, One Hundred and Twenty-second, One Hundred and Twenty-third, One Hundred and Twenty-fourth, One Hundred and Twenty-fifth, One Hundred and Twenty-sixth and One Hundred and Twenty-seventh Regiments of Infantry (Albany: Oliver A. Quayle, State Legislative Printer, 1904), 672, http://dmna.state.ny.us/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/Infantry/125th_Infantry_CW_Roster.pdf

Case of Stephen Zoller: Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York For the Year 1897. Register of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Artillery in the War of the Rebellion (New York and Albany: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1898), 420, http://dmna.state.ny.us/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/Artillery/16thArtCW_Roster.pdf

Case of Peter Jacot: Illinois. Military and Naval Department, Jasper N. Reece, and Isaac Hughes Elliott. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois, Volume VIII. Containing Reports for the Years 1861-1866 (Springfield: Journal Company, Printers and Binders, 1901. GoogleBooks), 543

Case of William Hoerhold: Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York. For the Year 1904. Registers of the One Hundredth and Forty-Seventh, One Hundred and Forty-Eighth, One Hundred and Forty-Ninth, One Hundred and Fiftieth, One Hundred and Fifty-First, One Hundred and Fifty-Second, One Hundred and Fifty-Third, One Hundred and Fifty-Fourth, and One Hundred and Fifty-Fifth Regiments of Infantry (Albany: Brandow Printing Company, State Legislative Printers, 1905), 598, http://dmna.state.ny.us/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/Infantry/150th_Infantry_CW_Roster.pdf