"Come and Go with Us": Legacies of Union, Freedom, and Civil War at Yorktown

/Thomas Osborn, of the 1st US Artillery, reflected as the Union army waited to advance along the Virginia Peninsula, “We are occupying the same ground which Washington and Lafayette occupied 81 years ago. . .Washington captured the Army then in Yorktown. Shall we capture the one now in it? We shall see.” In his observation, Osborn illustrated the irony that was surely on the minds of many soldiers as they expectantly looked for the outcome of the Union’s siege at Yorktown in the spring of 1862. The Confederate Army held the town that had long been canonized as the place Washington won the American Revolution. Less than one hundred years later, the country the Continental Army had fought for was at risk of irrevocably falling apart. When the Confederate Army retreated from Yorktown under the cover of night, the answer to Osborn’s question became clear, though the final outcome of the war far less so. Yet with their retreat, and the subsequent Union occupation of Yorktown for the rest of the war, the success of this siege had far more deep implications for the legacies of Yorktown and the Revolution.

Union occupation of Yorktown in the spring of 1862 came at the same moment that federal policy towards runaway slaves was reaching a breaking point. Just as slaves had already begun flocking to Fort Monroe, further east along the Peninsula, the Union Army’s presence encouraged runaway slaves, to settle in and around Yorktown. By July of 1863, Union General Isaac Jones Wistar took stock of the situation, observing, “Besides the dirty, idle, and neglected troops, were gathered over 12,000 refugee negroes supported in idleness on Government rations. . . in every stage of filth, poverty, disease, and death. . . The roadways, parade ground, gun platforms, and even the ditches and epaulements were encumbered by these poor wretches." Unable and unwilling to continue to tolerate these conditions, Wistar ordered able-bodied freedmen to build their own cabins outside of the Union fort at Yorktown. Their labors yielded a sight that had become common along the Peninsula: a town of freedmen. Many soldiers referred to these communities with the generic name, "Slabtown," because of the appearance of their buildings. At Yorktown, residents knew their home as “Uniontown,” a name that not only allied their cause with the army that now protected their freedom, but also resonated with the legacy of the Union established at Yorktown eighty years prior.

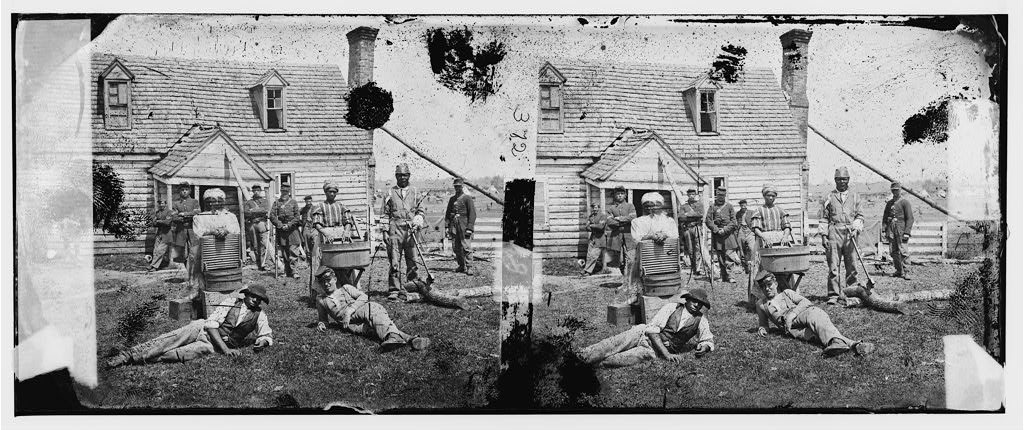

A group of "contrabands" at Yorktown. Library of Congress.

Archie Booker, an ex-slave living on the Peninsula during the war, remembered, “When the Civil War come, I followed the army back. It was then that I saw the battle of Yorktown. . . A great number of slaves followed the army around. Government supported them.” Indeed, by the end of the war, more than 40,000 (by some counts 70,000) freedpeople had settled on the Peninsula. Their presence created a striking sight for visitors who ventured to Virginia to see what the war had wrought. Whitelaw Reid noticed how Revolutionary images had become mixed with a new picture of the United States, observing, “Bricks, two centuries old, imported by the early colonists from Great Britain, for the mansions of the first families, were built up into little outside chimneys for these cabins of the Freedmen; and here and there one noticed an antique Elizabethan chair, of like age and origin, converted to the uses of a portly negress.” Though Reid did not mention it, his observation carried all the more meaning, if one considers that slaves were likely the ones who placed those bricks for the mansions of the first families and now former slaves reclaimed them for their homes.

John Trowbridge also visited, and his observations painted a drastically different image than the one Wistar had observed just two years earlier. He noted neat villages of freedman, hard at work laboring and fishing to provide for their families. Yet, according to Trowbridge, “They had but one trouble: the owners of the lands they now occupied were coming back with their pardons and demanding the restoration of their estates.” In 1866, Bayley Wyat, a resident of Uniontown, advocated for continued support of the new communities. Claiming a divine right to the land, he asked the Friends Association of Philadelphia and its Vicinity for the Relief of Colored Freedmen, who had been assisting at Uniontown, not to give up their support. Of the federal government Wyat explained, “Dey told us dese lands was 'fiscated from the Rebs, who was fightin' de United States to keep us in slavery and to destroy the Government. De Yankee officers say to us: ‘Now, dear friends, colored men, come and go with us; we will gain de victory, and by de proclamation of our President you have your freedom, and you shall have the 'fiscated lands.'" Yet, the promise had not been kept, as Wyat explained, “now we feels disappointed dat dey has not kept deir promise. O educated men! men of principle, men of honor, as we once considered you was! Now we don't seem to know what to consider, for de great confidence we had seems to be shaken, for now we has orders to leave dese lands by the Superintendent of the [Freedmen's] Bureau.” At Yorktown, freedpeople attempted to resolve this problem by pooling money and buying land outright. As a result of their efforts, Uniontown persisted. The continued presence of freedpeople on the landscape though, and the activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau in continuing to support schools and churches, proved to be points of conflict for their defeated white neighbors.

Violence pervaded life on the Peninsula, and Yorktown was not exempt. On May 23, 1866, the Assistant Superintendent of York County for the Freedmen’s Bureau reported that a “colored school” had been burned. Elsewhere, down the road at Norfolk, Bureau employees reported a riot that resulted in the murder of African Americans celebrating the passage of a civil rights bill. In Portsmouth, Kell Diggs, a white man, shot Samuel Ellis, a black man, that same month.

Graves of the uniontown community, outside the walls of the yorktown national cemetery (the back wall of the cemetery is visible in the right-hand side of the image)

Despite these challenges, residents of Uniontown would leave new and indelible marks upon Yorktown’s landscape. Their community would grow, and for decades after the war the black population of York County would outnumber whites. Uniontown residents visibly tied their memories to that of Union victory by burying their own dead in the shadow of the Yorktown National Cemetery, established during the war and included in the official system of federal cemeteries after the war. Moreover, though Yorktown would fade out of public view in the following decades, the black community at Uniontown would continue to remember and celebrate the new legacies of freedom wrought by the war through parades, speeches, and memorial activities. Yet Wyat’s words would also prove prophetic, as the federal government would eventually fully default on its promise to leave land in the hands of freedpeople, taking it back one hundred years later to include their lands in National Park Service holdings.

Becca Capobianco received her M.A. in U.S. and public history from Villanova University and is currently a PhD student at the College of William and Mary. She also works as a park ranger and has served as an educational consultant for the National Park Service. ©

Sources and Additional Reading:

Bragdon, Kathleen, Bradley M. McDonald, and Kenneth E. Struck. “Cast Down Your Bucket Where You Are”: An ethnohistorical study of the African-American community on the lands of the Yorktown Naval Weapons Station, 1865-1918. Atlantic Division, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Norfolk, Virginia, 1992.

Brasher, Glenn David. The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans in the Fight for Freedom. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Goldberg, Sarah. "Repatriating Yorktown: The Politics of Revolutionary Memory and Reunion." University of Chicago, 2010. Unpublished dissertation.

Reid, Whitelaw. After the War: A Tour of the Southern States, May 1, 1865, to May 1, 1866. Sampson Low, Son, & Marston, 1866.

Trowbridge, J.T. The Devastated South, 1865 - 1866: A Picture of the Battlefields and of the Devastated Confederacy. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1956.

Wyat, Bayley. “A Freedman’s Speech. Philadelphia.” Friends’ Association ofPhiladelphia and Its Vicinity for the Relief of Colored Freedmen, 1866. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.1590140b/.