The Great Locomotive Chase: Part II, The Chase

/The raiders awoke early and met in Andrews’ room to go over their plans. They would board a train at Marietta and when the train stopped at Big Shanty for a breakfast stop they would uncouple the cars and take the engine. In the end, only twenty of the group ended making the raid—Hawkins and Porter overslept and missed the group’s departure. This was detrimental to Andrews’ plan because Hawkins was the most experienced engineer and was supposed to be in charge of the engine once they stole it.

The raiders boarded a train consisting of a locomotive—The General—and its tender, two passenger cars, a baggage car, and three box cars. The General’s conductor was twenty-five-year-old William Allen Fuller with engineer E. Jefferson Cain and fireman Andrew Anderson. With the first leg of the trip mostly uneventful, the train stopped as planned at Big Shanty and the passengers and crew unloaded for breakfast. Fuller was particularly on edge that morning—one of his supervisors, Anthony Murphy, foreman of motive and machine power on the Western & Atlantic Railroad, was riding as a passenger on that train and Murphy sat down with the crew for their breakfast.

With the rest of the passengers off the train, Andrews and Knight walked to the front of the train to check the engine. With the crew sitting down to breakfast, Andrews readied the engine while Knight detached the baggage and passenger cars from the train. They decided to keep the three box cars attached to the locomotive—if they were questioned their story was that they were an emergency ammunition train needed at Corinth by way of Chattanooga, which would explain why they were rushing north with no passengers. Having made their preparations—all within view of Confederate soldiers stationed at the adjacent Camp McDonald—the two men retrieved the others and took their places. Knight took control of the engine with Andrews with him, Wilson climbed into the first boxcar to serve as brakeman, and the others piled into the last boxcar.

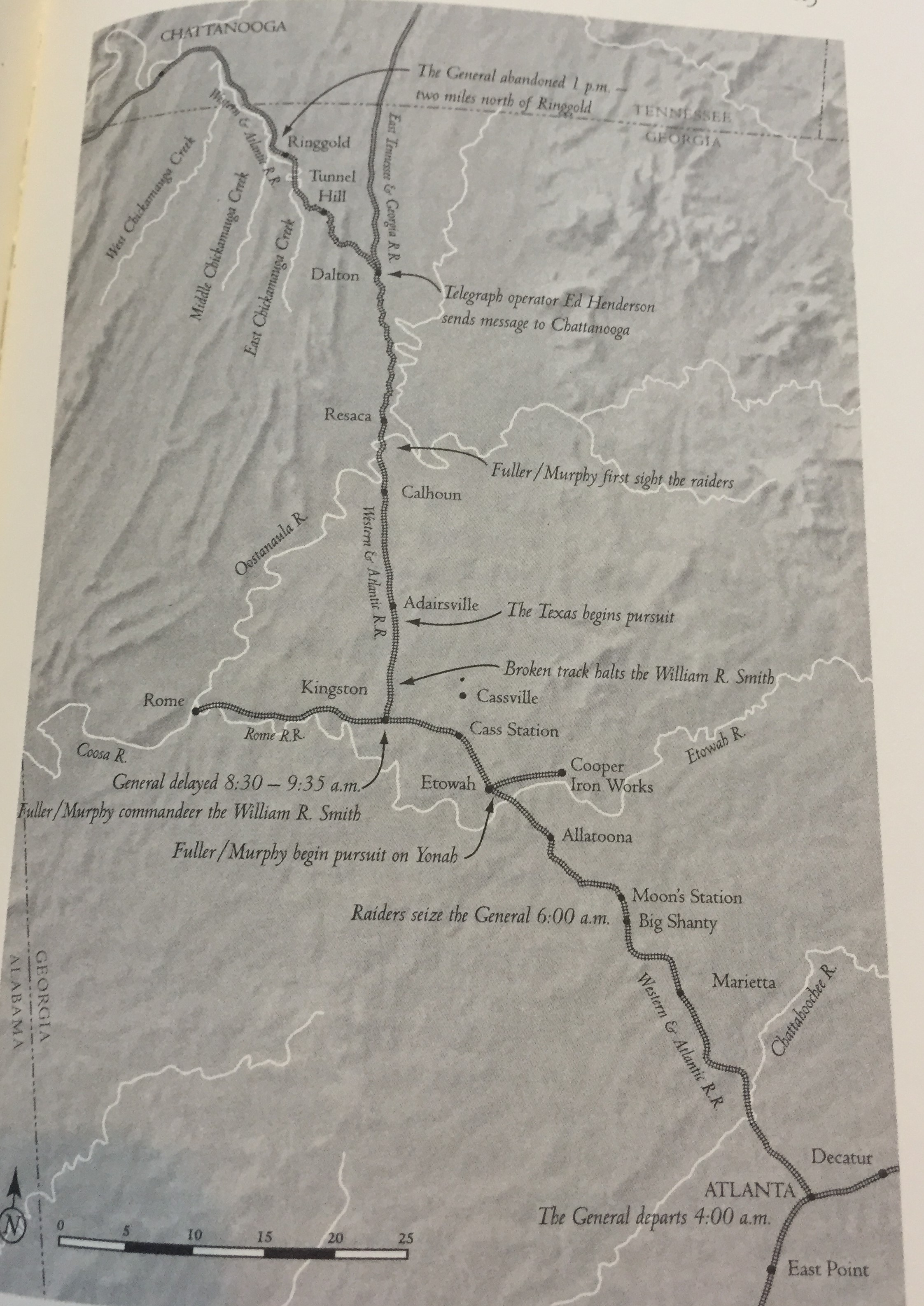

The crew was sitting down to their breakfast when they heard the sounds of the engine and saw it start to pull away from the station. A local resident rode off toward Marietta, and the nearest telegraph, to alert authorities, but William Fuller knew the train would be long gone before the word went out. Fuller took off after the train on foot, followed by his engineer, Cain, and Anthony Murphy. The “Great Locomotive Chase” had begun.

Andrews’ plan was to travel as normal as possible to avoid detection, particularly through stations, so he went at a normal speed to keep on the original timetable and stopped only in between stations to cut telegraph wire or obstruct the track with railroad ties. The Raiders ran into trouble in their plans to destroy the tracks because they had not been able to bring the necessary tools with them, but they did pull down the wires using the train’s momentum.

Behind them, Fuller and his party struggled to catch up. The rider sent towards Marietta managed to telegraph the superintendent of the railroad, E. B. Walker, who ordered another conductor to take the Pennsylvania to Big Shanty, gather soldiers there, and follow the General. This ended up taking so long that by the time the Pennsylvania was ready to pursue, the Chase was already over. For now, Fuller, Cain, and Murphy were on their own. Once the three reached the next station at Moon’s Station, they borrowed a hand car (along with two other men joining them) to continue the chase. This was a pole care where workers used long poles to move themselves along, not a “seesaw car” as depicted in the film.

Meanwhile, the General continued its way north past Allatoona, Etowah, Cass Station, and approached Kingston, a larger junction station. At the same time, Mitchel also moved ahead and captured Decatur and the bridge over the Tennessee River. So far the plan to approach Chattanooga from two directions was succeeding. But not for long.

The General was hung up at Kingston due to extra trains coming south along the one-way track. This was an unfortunate result of Andrews’ own plan; the extra trains were bringing supplies out of Chattanooga because Mitchel was threatening the city. The Raiders had to wait for three extra trains, about an hour of delay, before they could get back on the track north. Meanwhile, Fuller was starting to catch up. Having poled the hand car from Moon’s Station to Etowah he convinced the crew of the Yonah to use the locomotive in their pursuit. They managed the fourteen miles from Etowah to Kingston in fifteen minutes where they traded the Yonah for the William R. Smith and continued the chase.

Fearing pursuit from the South after the delay at Kingston, the General’s crew moved faster, stopping only twice to cut wires and damage the track. At Adairsville, the General pulled into a siding alongside the Texas. Still trying to avoid detection, Andrews did not move to disable or stop the other locomotive, instead chatting about the southern train both were waiting for to pass. The south-bound train being so late, the engineers of both locomotives decided to continue on their way. The Texas moved back onto the track to go south and the General continued (dangerously) north hoping they would not run into that late-running train on the single track.

At this point Fuller was on the verge of catching up. Abandoning the William R. Smith where the Raiders had damaged the track, Fuller and Murphy continued on foot until they met the south-bound Texas. Explaining the situation, the Texas’s engineer backed the locomotive back to Adairsville, dropped off its load of cars on the siding, and raced north to catch the General, backwards.

The Raiders had stopped again to disable the track, but the Texas caught up to them. Panicked, the Raiders dropped one of their boxcars (which the Texas just coupled up to their tender unfazed) and raced North. Because the pursuit was so close, the Raiders could not stop to burn their first major objective, the Oostanaula River bridge, which would had stopped any pursuit from the south. The Raiders dropped a second box car, hoping to delay the Texas, but the Texas quickly pushed it to a siding and continued on. At Dalton, Fuller dropped off a telegraph operator whom he had picked up at an earlier station to send a message to Chattanooga. Alerted to the stolen engine, General Danville Leadbetter sent a Confederate force to meet the Raiders eleven miles from the city; they tore up the track and waited for the General.

At this point the Raiders were struggling. Fuller was hard on their heels with the Texas, they were running out of fuel, and, unbeknownst to them, there was now a Confederate force waiting for them. Just past Ringgold, after nearly 89 miles, the General ran out of steam. Andrews ordered his men to scatter and flee while Fuller triumphantly reclaimed its engine and towed it back to safety at Ringgold. Fuller had followed his engine the entire way, first on foot, then with the hand car, and then with three successive engines, ending with the Texas which chased the General for 48 miles backwards.

The “Great Locomotive Chase” had come to an end. But the story was far from over…

Read the rest of the series here.

Further Reading:

Bonds, Russell S. Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2007.

Pittenger, William. Daring and Suffering: A History of the Andrew Railroad Rail. Cumberland Publishing House, 1999.

Rottman, Gordan L. The Great Locomotive Chase: The Andrews' Raid, 1862. New York: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 2009.

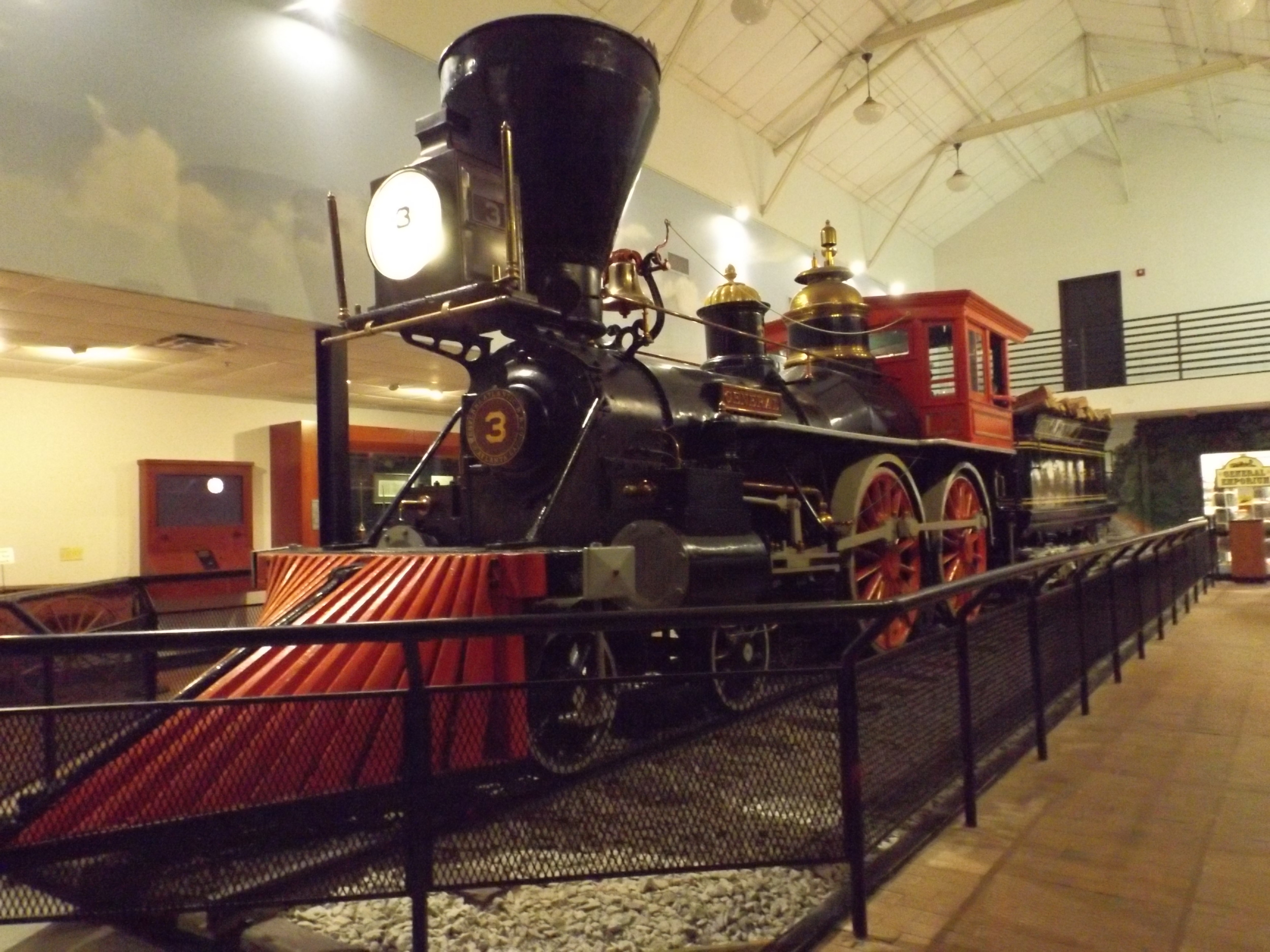

The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in Kennesaw, GA has an extensive exhibit on the Andrews' Raid, including the restored General.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen was a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park from 2010-2014 and has worked on various other publications and projects.