Should Indian Territory Be Considered a Border State?

/Earlier this month at the Society of Civil War Historians' conference in Chattanooga, I engaged with two panels that sparked new lines of thought for me regarding the Civil War and my own area of study—the Civil War in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma). The first panel—on which I had the good fortune of presenting—discussed the war in Indian Territory specifically, and after our presentations the audience and panel engaged in a lively discussion regarding the place of Indian Territory (or its lack thereof) within current scholarship. It was the kind of discussion a panelist can only dream about. The second panel—a roundtable aptly entitled “Go West, Young Historians! Expanding the Boundaries of Civil War Studies”—prodded around a wide variety of ideas regarding the West and the Civil War. At one point in this freewheeling discussion, a panelist suggested that we should perhaps begin thinking about the entire Southwest as a border region, since proponents of both free-soil and slavery migrated to, cast their designs upon, and struggled over the fate of the region.

I was taken by this idea. When historians speak of the border between North and South, they usually mean the Potomac and Ohio Rivers, and the well-known “border states” of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. But while the “border state framework” (as I’ve come to call it) often stops along the Missouri-Kansas line, the actual border (and borderlands) between North and South did not—it continued westward through Indian Territory, down into New Mexico/Arizona, and perhaps, as the panelist suggested, even further west to California or north into the Great Basin and Pacific Northwest.

These broad thoughts swiftly came full circle back to my own research, and I began to wonder…

Should we consider Indian Territory a border state?

An important question, I think. If we begin to envision the borderland between the Union and Confederacy as something more than the regions along the Potomac and Ohio Rivers (with Missouri thrown in), we should be able to make the case that more border states (or border territories!) existed. And in acknowledging their existence, perhaps we can better connect the Civil War West to the Civil War East.

And what better place to begin than Indian Territory itself? Isn’t Indian Territory a border state?

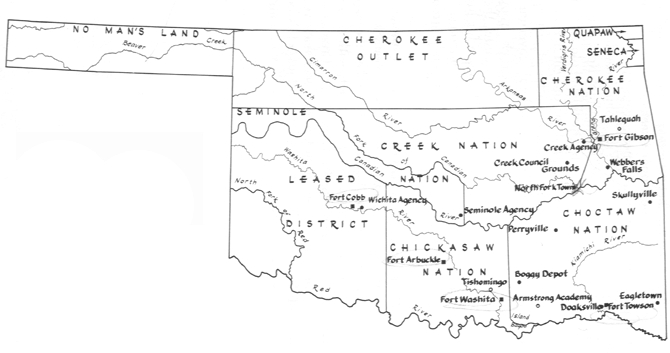

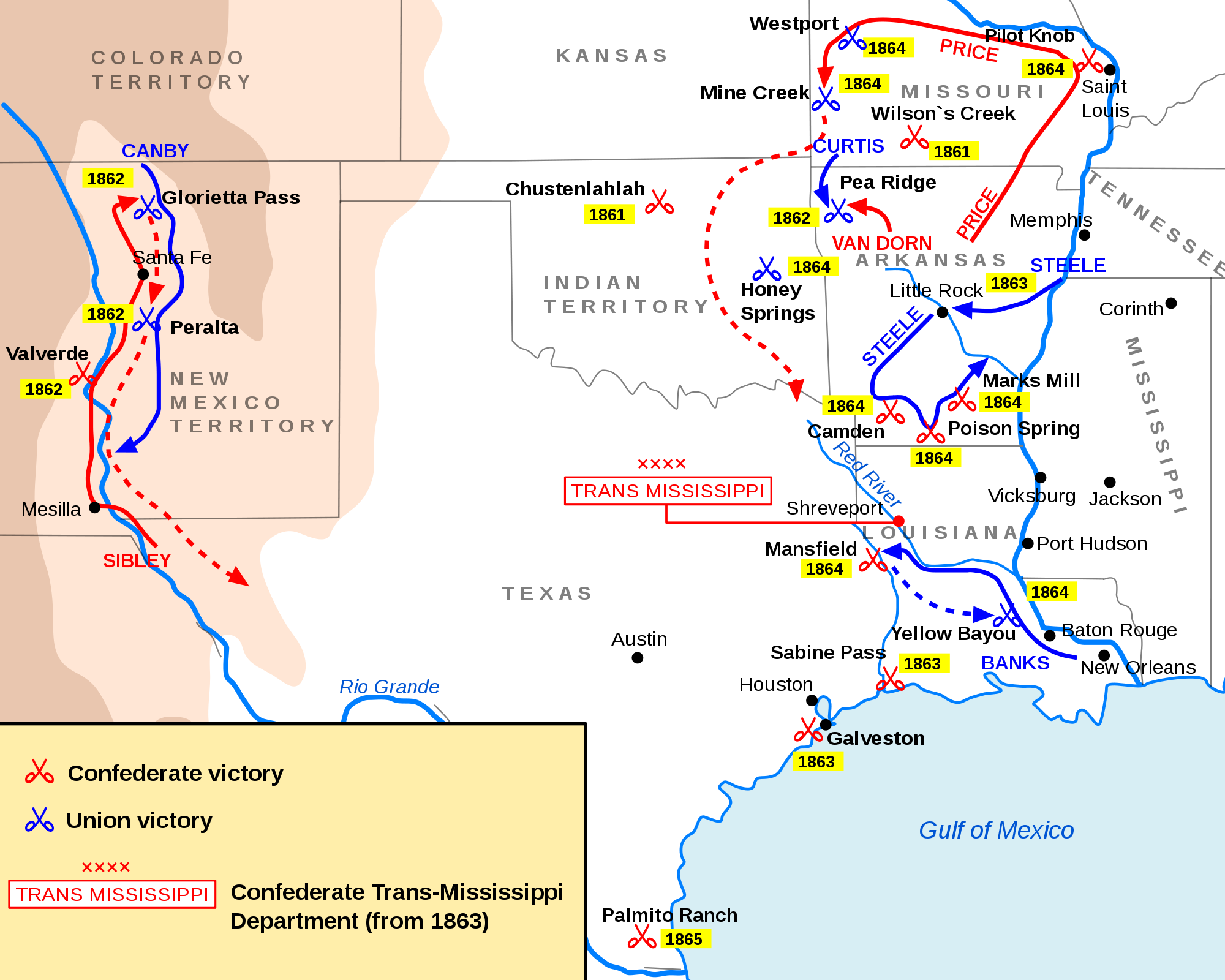

After all, although not actually a state, Indian Territory nevertheless possessed the feature that most defined border states: it sat along the border. Just like its eastern counterparts in Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, Indian Territory found itself along a dangerous geopolitical fault line in 1861, trapped between north and south as the nation fell apart. A cursory glance at a map shows that Indian Territory was nestled in between Union Kansas to the north, another badly-divided border state in Missouri to the northeast, Confederate Arkansas to the east proper, and Confederate Texas to the south. Just as geography practically guaranteed that states like Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland would be swept into the maelstrom of civil war, the geography of Indian Territory likewise meant that its denizens would have to navigate the dangerous political and military currents that surrounded it.

Far more than simple geography, however, linked Indian Territory to the other border states. The political and cultural institutions among the Territory’s denizens also mirrored, to a degree, those found elsewhere along the border. In 1861, eastern Indian Territory was the home to the Five Tribes: Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. These Native-American tribes possessed centuries of experience dealing with first European, then American, governments and societies, and they had likewise undergone long processes of acculturation. Forced to remove westward in the early 1800’s, most infamously along the “Trail of Tears,” these Indian tribes had built new homes in the west. They elected legislatures and principal chiefs (roughly akin to governors), appointed judges, maintained police forces, allowed missionaries of varying stripes to proselytize and open schools, tilled the land in farms both small and large, and traded with their white neighbors along the Arkansas and Red River basins. The sons of prominent Indian families often went to college in the South, and the wealthiest Indians maintained plantations and mansion homes worthy of any Southern planter. Cherokee leaders belonged to both antislavery societies and the Knights of the Golden Circle. Other Indians joined temperance groups, Bible societies, and the Freemasons. Newspapers like the Choctaw Intelligencer in Doaksville and the Cherokee Advocate in Tahlequah offered news from around the nation and the Atlantic world, and they hawked goods from New Orleans and Little Rock. Indians within the Territory had adapted to, and interacted with, wider America, especially the South.

Long centuries of acculturation also meant that the Five Tribes practiced the institution of slavery. Allow me to play with numbers for a moment. In 1860, Indian Territory (meaning the Five Tribes collectively) possessed a population of 58,894 (about half the size of Kansas' population and a bit larger than that of Oregon Territory). The 47,927 Indians belonging to the Five Tribes constituted 82% of the Territory’s population, 2,299 whites allowed to reside in the Territory comprised 4% of the population, and 8,376 slaves held in bondage accounted for 14% of the population. The proportion of enslaved persons in Indian Territory—14.2%—bears striking resemblance to the proportion of slaves held in other border states (MO, KY, MD, DE), where slaves comprised 12.7% of the population collectively. It is worth noting, however, that in Indian Territory these thousands of slaves were concentrated in the hands of a relative few; only 2.3% of Indians owned slaves in 1860. This figure contrasts with higher rates of ownership in Kentucky (23%), Missouri (13%), and Maryland (12%). Only Delaware’s 3% slave ownership rate is comparable. Still, the large number of actual slaves in Indian Territory, the overall enslaved percentage of the population, and the importance of slavery to Indian leaders are qualities that fit squarely alongside slavery's role in other border states.

Moreover, among the white population in Indian Territory born outside the Territory, almost all—75%—hailed from the slave-owning south, and most of those—36% —were born in the western border/Upper South region (Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky, or Tennessee). When Indians interacted with white neighbors, either inside the Territory or across state lines—they were interacting with slave-owning Southerners, mostly from the border/Upper South.

To be sure, slavery did not define Indian culture, and the various cultural practices of the Five Tribes differed sharply from those of white residents in, say, Missouri or Maryland. Many members of the Five Tribes danced in the Green Corn Ceremony (for a good corn harvest), dressed in traditional Indian hunting garb, and bore names like Halek Tustunegee or Opothleyahola. These cultural differences are important, and they cannot be overlooked. Yet in my opinion, these cultural differences do not warrant cause for exclusion from the border state frame of analysis, especially when one considers the long process of acculturation and the institutions—including slavery—shared between the Five Tribes and the South. I suspect, if we continue our border state framework even farther into the Southwest, we will find more diverse Indian and Hispanic cultures coming into play; again, I think these differences don't warrant exclusion, but instead beg for inclusion.

As is often pointed out, Indian Territory did not exhibit the same geopolitical or strategic importance of other border states back east. If the Lincoln administration worried incessantly about the fates of Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky (as Lincoln exclaimed, "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky"), they showed how little they cared about Indian Territory when they promptly evacuated Federal troops there in May, 1861 (a move that opened the door for Confederate overtures to Indians). Richmond showed only a little more interest in Indian Territory.

Yet for people living in this region of the Trans-Mississippi, the political loyalties of their Indian neighbors were tremendously important, and more relevant to their lives than the fates of Kentucky or Maryland. Following Lincoln's election, counties in western Arkansas proved reluctant to secede without first knowing the intentions of their Indian neighbors. The citizens of Boonsboro wrote directly to Cherokee Chief John Ross, asking about Cherokee politics and noting they preferred "an open enemy to a doubtful friend." Arkansas Governor Henry Rector likewise wrote Ross, express his hope "to find in your people friends willing to co-operate with the South in defense of her institutions, her honor, and her firesides." Texans also took an interest in Indian affairs and were more direct about securing their friendship. In the spring of 1861, Texan militia rode north across the Red River to secure the forts abandoned by the U.S. army in Indian Territory, and Texan vigilantes prowled the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations in search of any abolitionists and pro-Northern men. White southerners west of the Mississippi recognized the importance of Indian Territory as a border region; so should we.

We must also recognize that Indians themselves experienced divided loyalties during the Civil War, despite Southern pressure to ally with the upstart Confederacy. Just as families and communities in Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland struggled with the prospect of war, and with whom they should side, so too did Native-Americans grapple with hopes of peaceful neutrality, realities of war, and intra-community violence. In 1861, many Native-Americans sought to stay out of the looming Civil War, hoping to continue to peacefully abide under their existing treaties with the United States government. For a variety of reasons (explained ably by the scholars listed in the bibliography below), the Five Tribes one-by-one allied with the Confederate States, although it is worth noting that the Cherokee Nation under Chief John Ross made a sincere attempt at neutrality which lasted until the autumn of 1861. Yet whatever the paper treaties declared, Native-American loyalties proved divided, even to the point of intra-tribal warfare. By the fall and winter of 1861, thousands of Creeks, Seminoles, free and enslaved blacks, and others had gathered under Creek chief Opothleyahola in resistance to Confederate authority (many of Opothleyahola’s warriors would later constitute the heart of the Union Indian Home Guard regiments). By 1862, the Creeks, Cherokees, and Seminoles had splintered. Thousands of Indians fought in both blue and gray. Just as it did in other border states, the Civil War tore Indian Territory apart.

Although undoubtedly the divided politics of the Five Tribes owed itself more to simmering feuds over removal and schisms between traditionalist/progressive Indians than preserving the Union or protecting slavery, the divided nature of the population and the accompanying localized guerrilla war clearly bear resemblance to the experiences of other border states, most notably Missouri and Kentucky. Just as a movement for neutrality found support in Kentucky but ultimately failed, so too did many Indians aspire to stay out of the war, yet simply could not. And the resulting violence, which pitted tribes and communities against their own kind, parallels (if not exceeds) the kind of violence found in back-country Missouri and the hills and coves of Appalachian Kentucky and western/West Virginia.

Perhaps the most persuasive argument for including Indian Territory into our scholarship is the sheer destruction reaped upon Native-Americans during the Civil War. One-third of the Cherokee Nation perished in the American Civil War. One-quarter of the Creek Nation perished, too. By war’s end, roughly 30,000 individuals—nearly 60% of Indian Territory’s population—were refugees. These terrible figures attest, in part, to the brutal guerrilla warfare and intra-community violence that haunted the Territory’s landscape from 1861 to 1865. And it is perhaps because Indian Territory has long been excluded from many aspects of Civil War historiography that so few are aware of the brutality of the Civil War in Indian Territory.

I could count on two hands the number of serious, scholarly works that have examined Civil War Indian Territory in the past century, although the addition of several volumes in the past few years gives me hope that the Territory’s pitiful historiography is undergoing a mini-renaissance, of which I want to be a part. And of which you should be a part, too.

And although I have argued here that we should include Indian Territory in border state frameworks, in reality, I think we—Civil War scholars and academics, buffs, public historians…everyone who cares about or seeks to understand the Civil War—should increasingly include Indian Territory and Native-American perspectives in our study of the Civil War. Even more broadly, we should continue to find ways to connect the Civil War in the West to the Civil War in the East, we should not be afraid to extend our lines of analysis westward, and I think comparative border state/borderlands/guerrilla studies are a fine place to start.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Further Reading & Sources:

Abel, Annie Heloise. The American Indian as Slaveholder and Secessionist. 1915. Reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

Arenson, Adam and Andrew R. Graybill, eds. Civil War Wests: Testing the Limits of the United States. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.

Clampitt, Bradley R., ed. The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Confer, Clarissa. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

Cowsert, Zachery C. "Confederate Borderland, Indian Homeland: Slavery, Sovereignty, and Suffering in Indian Territory." M.A Thesis. West Virginia University, 2014. (I'm citing myself...I couldn't help it)

Doran, Michael F. "Population Statistics of Nineteenth Century Indian Territory." Chronicles of Oklahoma 53, no. 4 (1975): 492-516.

---. "Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 68, no. 3 (Sept., 1978): 335-350.

Gaines, W. Craig. The Confederate Cherokees: John Drew's Regiment of Mounted Rifles. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Hauptman, Laurence M. Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War. New York: The Free Press, 1995.

Josephy Jr., Alvin M. The Civil War in the American West. New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

Krauthamer, Barbara. Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Minges, Patrick N. Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855-1867. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Smith, Troy. "Nations Colliding: The Civil War Comes to Indian Territory." Civil War History 59, no. 3 (Sept., 2013).

Warde, Mary Jane. When the Wolf Came: The Civil War and the Indian Territory. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2013.

White, Christine Schultz and Benton R. Now the Wolf Has Come: The Creek Nation in the Civil War. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1996.

Yarbrough, Fay A. Race and the Cherokee Nation: Sovereignty in the Nineteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.