"Wrap the World in Fire," Part I: The Possibility of British Intervention in the American Civil War

/Part I in a series; read part II and part III here.

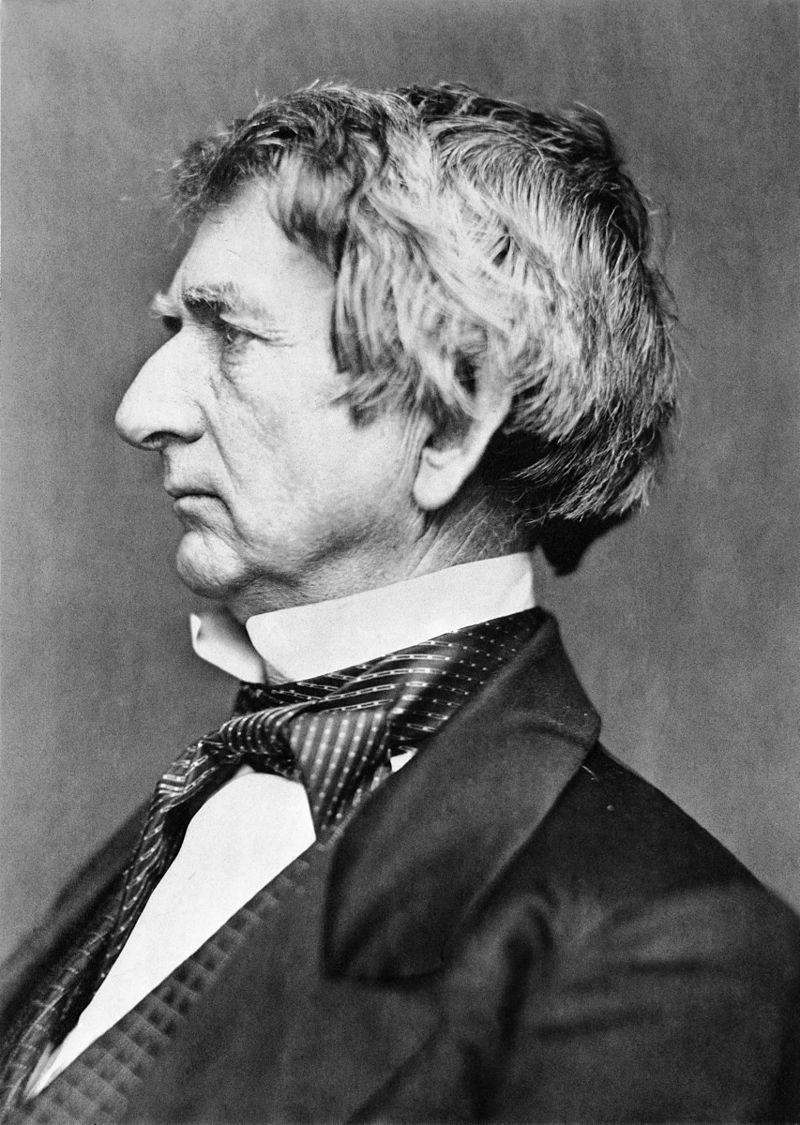

“If any European Power provokes a war, we shall not shrink from it. A contest between Great Britain and the United States would wrap the world in fire.” United States Secretary of State William Seward uttered these bold words in the summer of 1861, while his nation tore apart at the seams. Yet despite the secession of eleven Southern states, Seward pondered the possibility of war with Great Britain, the world's foremost power. Why?

The answer lies in the high-stakes game of diplomacy that was played by both the Union and Confederacy with Great Britain during the American Civil War. For the Union, foreign intervention in the conflict was a constant threat, one that might ensure Southern independence. Conversely, the Confederacy constantly sought and expected foreign recognition and intervention, seeking support and validation for their secession. In a series of three posts, I want to examine the topic of British intervention in the American Civil War. In today’s brief primer, I take a look at the possible reasons for British involvement in the conflict. Future posts will examine both Union and Confederate foreign policy strategies and their effectiveness with Great Britain.

To understand the importance of American (Northern and Southern) and British foreign relations during the Civil War, we must begin by looking at possible motivations for British intervention. Were Union fears and Confederate hopes regarding British intervention justified? Obviously, Great Britain did not (officially) intervene in the American Civil War, but the possibility certainly existed. There three British rationales for intervention in the American conflict.

First, intervention may have arisen out of Great Britain’s own self-interest, primarily concerning the economic ramifications of the war. While the Civil War proved devastating to America, it also caused considerable economic woes overseas. While the details of this economic depression will be accounted for later, suffice it to say that Great Britain suffered significantly due to the unavailability of cotton for its textile markets. Under international law at the time, a neutral state could intervene in a foreign civil war when its own welfare was endangered. As The Economist’s editor of the day pointed out regarding the war's economic consequences, “We participate in the ruin that is going on…We have, therefore, a right to speak and to be heard.” With Britain’s economy suffering directly from the war in America, Britain may have had an economic andlegal pretext to intervene in the conflict.

Second, there was a strong belief among British leadership that Great Britain had a humanitarian duty to help end the conflict. Again, international law claimed that nations had an obligation to help the combatants avoid “disaster and ruin, so far as it can do without running too great a risk.” As the world’s premier power, perhaps Britain moral duty to try to find an end to the increasingly bloody struggle. As the London Morning Herald pleaded in September of 1862, “Let us do something, as we are Christian men…Let us do something to stop this carnage.” Further, most British considered the Union cause futile—there was no way the entire American South could be subjugated and brought back to the fold; this disbelief that the Union could be welded back together led to the conclusion that mediation between the parties (mediation based on separation) was a logical, humane policy.

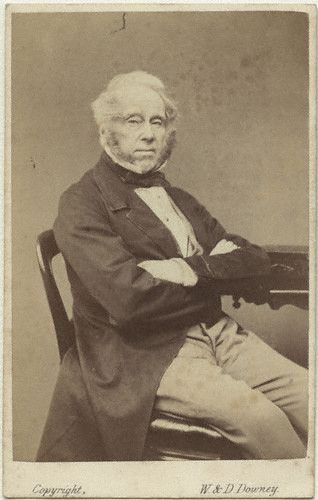

Finally, British involvement could perhaps come as the result of unforeseen events...international crises and scenarios that unexpectedly placed the island on a path to war. Perhaps the best example of such a perilous breakdown is the infamous Trent Affair. In late 1861, a U.S. warship boarded the British steamer Trent and arrested two Confederate envoys on board who were headed for Europe, an action viewed by many as a violation of international law. The affair immediately heightened tensions between the United States. and Great Britain, who viewed the boarding as a violation of British sovereignty. Indeed, an American in London at the time wrote to Secretary Seward, “The people are frantic with rage, and were the country polled, I fear 999 men out of a thousand would declare for immediate war.” The insult to British honor caused by the U.S. Navy seemed likely to spark a war. Britain responded to the incident by issuing a seven-day ultimatum demanding an explanation and the release of the Confederate prisoners. Despite the popularity of the Navy’s actions at home, President Abraham Lincoln conceded to British demands and defused the situation, releasing the prisoners and having Secretary Seward issue a note of explanation. In a personal letter to friends, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston reveals both the satisfaction the apology provided and just how perilously close war had come: “If we had not shewn [sic] that we were ready to fight, that low-minded fellow Seward would not have eat the leek as he has done.”

The possibility of British intervention in the American Civil War was very real. Whether due to economic interests, humanitarian pleas, or international incidents, both the Union and Confederacy had to grapple with the prospect of Europe intervening in and perhaps deciding the American conflict. Considering Great Britain's tremendous political and military might in the mid-nineteenth century, Abraham Lincoln and his administration faced an immensely important task in trying to keep Britain neutral. Next week's post will examine Union foreign policy with Great Britain further.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Further Reading and Sources

“America’s Bloodiest Day.” America’s Civil War 20.4 (Sept., 2007): 26-29.

Anderson, Stuart. “1861: Blockade vs. Closing the Confederate Ports.” Military Affairs 41.4 (Dec., 1977): 190-194.

Blumenthal, Henry. “Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities.” The Journal of Southern History 32.2 (May, 1966): 151-171.

Brauer, Kinley J. “British Mediation and the American Civil War: A Reconsideration.” The Journal of Southern History 38.1 (Feb., 1972): 49-64.

James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Jenkins, Philip. A History of the United States. 3rd ed. Ed. Jeremy Black. Willshire, U.K.: Palmgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Jones, Howard. Blue and Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations. Eds. Gary W. Gallagher and T. Michael Parrish. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait Through His Speeches and Writings. Ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher. New York: Signet, 1964.

Owsley, Frank Lawrence. King Cotton Diplomacy. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959.

Reid, Brian Holden. “Power, Sovereignty, and the Great Republic: Anglo-American Diplomatic Relations in the Era of the Civil War.” Diplomacy and Statecraft 14.2 (June, 2003): 45-76.

Temple, Henry John (Third Viscount Palmerston). The Letters of the Third Viscount Palmerston to Laurence and Elizabeth Sullivan 1804-1863. Ed. Kenneth Bourne. London: Royal Historical Society. 1979.

“Trent Affair.” Colombia Electronic Encyclopedia. 6th ed. 1 July 2010.