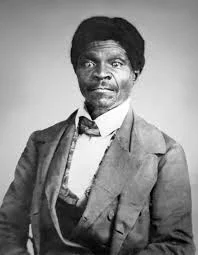

Suing for Freedom: The Dred Scott Case

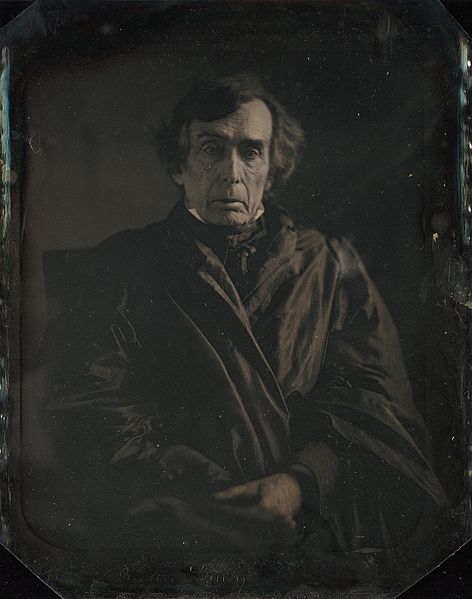

/In March 1857, the Supreme Court delivered a ruling that sent shock waves through the north. In the Court opinion delivered by Chief Justice Roger Taney, slaves were not considered citizens of the United States and could not sue in Federal Court, but more importantly Congress did not have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories. For free labor/free soil advocates in the north, this was a major step backwards in the efforts to contain the spread of slavery.

Everything centered on one man, a slave named Dred Scott. Scott was born at the end of the eighteenth century in Virginia and taken in 1820 to Missouri, where he was purchased by Dr. John Emerson. As a surgeon in the U. S. Army, Emerson moved around on assignment and brought Scott with him. First, Emerson took Scott to Fort Armstrong in Illinois, a free state whose 1819 constitution prohibited slavery. Then in 1836, Emerson moved again, bringing Scott to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was prohibited under the 1820 Missouri Compromise. During his stay there, Scott met and married Harriet Robinson who Emerson bought at the fort.

The next year, Emerson was ordered to Jefferson Barracks Military Post near St. Louis, Missouri. He left Dred and Harriet at Fort Snelling, hiring their labor out to others (a distinct practice of slavery). A few months later Emerson moved to Fort Jesup in Louisiana, married Eliza Irene Sanford, and sent for his two slaves to serve his new family. During the journey south, the Scotts welcomed a daughter, Eliza, who was technically born free under federal and state laws because she was born in a free state. By 1840, Emerson’s wife had moved back to St. Louis while Emerson served in the Seminole War. Three years later Emerson died, and Eliza inherited the estate, including the Scotts who she hired out.

In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase freedom for himself and his family. Upon Eliza Emerson’s refusal, Scott sued for his freedom in a Missouri court with the help of abolitionist legal advisors and the son of his first owner. He based the claim for freedom for himself and Harriet upon their residence in free territories, and the claim for Eliza on her birth in a free state.

The first suit was dismissed upon a technicality, but in the second trial (begun in January 1850) the jury found in favor of the Scotts and granted them freedom. Unwilling to lose her slaves, Emerson appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of Missouri. In late 1852, the state Supreme Court overturned the original decision declaring that the Scotts were still legally slaves and should have sued for freedom while they were living in a free state.

By this time Eliza Emerson had moved to Massachusetts and transferred ownership to her brother, John Sanford. In 1853, Scott sued again, this time basing his argument on the fact that John Sanford had moved to New York and was a resident there. Again, the jury found in favor of Sanford, basing their decision on the Missouri case.

Finally Scott appealed his case to the U. S. Supreme Court, still hoping to gain freedom for his family. The ruling handed down on March 6, 1857 was not only the last dash of hope for the Scotts, but shocked many people in the North.

The first opinion of the court, handed down by Chief Justice Roger Taney, was the Court did not have jurisdiction to review the case. They declared that Scott could not claim that he was a “citizen” because of his descent from an imported African slave. Going even farther, the Court declared that no person of African descent, whether in slavery or free, could be a citizen and thus could not bring a suit to federal court. Taney declared that the Founding Fathers who wrote the Constitution had viewed blacks as “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Even though the Court had decided they could not rule on the case, they continued on to the other questions presented in the case, those about the Missouri Compromise which Scott had based his claims to freedom on. Essentially, the Court declared the Missouri Compromise to be unconstitutional. Because the Louisiana Purchase was acquired after the Constitution was signed, Taney declared that Congress could not regulate the governments in that territory, nor could they violate the Fifth Amendment protection of property. Thus, even though the Scotts had lived in a free state, they were still slaves and could not claim emancipation.

With the Court’s decision, Taney had made game-changing remarks about American slavery. Not only were all African-Americans denied any claim to citizenship, even if they were emancipated or born free, the Missouri Compromise was overturned. As one in a series of political compromises created to maintain political balance in the country and prevent future conflict, the destruction of the Compromise opened the door for additional sectional strife. For free labor advocates in the north the decisions in Scott v. Sanford threatened to destroy the sanctity of the free territories in the North. If slaveowners could bring their slaves into free territories with no penalty, what would stop them from bringing slaves back into the northern states, and then reinstituting slavery in states that had already abolished the practice?

Southerners rejoiced at the Court’s decisions and Northerners saw dark clouds on the horizon. In a period of delicate political and sectional balance, the Dred Scott decision heightened Northern fears of a spreading institution of slavery. Coming in the last years before the secession crisis and Civil War, the Dred Scott decision was a sign that compromise was beginning to break down between North and South.

While the nation buzzed with reactions to the Court’s ruling, the decision was a personal tragedy for the Scott family. Having pursued their freedom for a decade, they had finally exhausted their legal options and remained enslaved. Fortunately, the sons of their first owner, Peter Blow, had helped them with their legal cases and now purchased emancipation for Scott and his family in late May 1857. Scott worked in a St. Louis hotel until his death of tuberculosis in November 1858 and Harriet died in 1876. Both are buried together in St. Louis’ Calvary Cemetery. Today a monument to Dred and Harriet stands outside the courthouse where they first filed their suit for freedom. Together they gaze at the Arch, a symbol of the western expansion so crucial in their lives and claims for freedom.

Suggested Reading:

Fehrenbacher, Don. The Dred Scott Case, Its Significance in American Law and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Freedman, Suzanne. Roger Taney: The Dred Scott Legacy. Springfield, NJ: Enslow Publishers, 1995.

Konig, David Thomas, Paul Finkleman, and Christopher Alan Bracey. The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010.

Maltz, Earl. Dred Scott and the Politics of Slavery. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.