Slavery? States Rights? Secession.

/A few years ago I attended a session at the American Association for State and Local History conference in Richmond, Virginia that caused me to reflect on the history we present to the public. The session, entitled “Secession and the Confederacy: Issues for Local History Sites,” focused on the fact that “many Americans still greatly misunderstand secession and the coming of the war” (taken from the session description). The panelists offered a wide range of backgrounds—Chair Dr. Marty Blatt is the Chief of Cultural Resources/Historian at Boston NHP, John Coski is the Director of Library and Research at the Museum of the Confederacy, James Loewen is a professor of sociology and author of The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader, and Dwight Pitcaithley is the former Chief Historian of the National Park Service—but all offered a united point of view on the cause of the Civil War: Slavery is the answer.

And they have a point. Many of the secession conventions and declarations specifically point to slavery as the cause of their secession. South Carolina, leader of the secession movement, speaks largely of the ability of independent states to break away from the Union and Constitution to protect their rights which could lead to the claim that state’s rights caused secession. The rights they are referring to? Slavery: “The right of property in slaves was recognized by giving to free persons distinct political rights, by giving them the right to represent, and burthening them with direct taxes for three-fifths of their slaves; by authorizing the importation of slaves for twenty years; and by stipulating for the rendition of fugitives from labor.” The government had broken its responsibility to uphold the fugitive slave law laid out in the fourth Article of the Constitution; since the agreement of the Constitution had been broken, the states had every right to break away to protect their interests. The declaration points to “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery, [which] has led to a disregard of their obligations” despite the Constitution’s affirmation and protection of slavery. Virginia’s Ordinance of Secession speaks to the “oppression of the Southern slaveholding States” and the second sentence of Georgia’s declaration states “For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slaveholding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery.”

Perhaps Mississippi said it best: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world…There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.” So yeah, secession was about slavery, whichever way you want to package it.

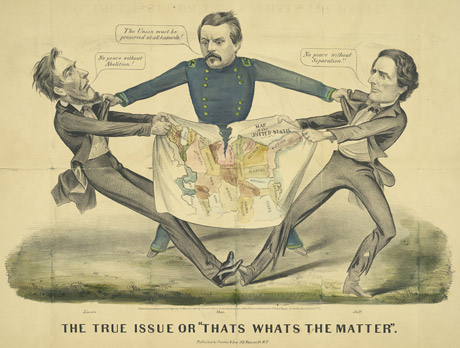

However, if you listen to the public slavery is one of a variety of answers, and it is not always the answer that comes first or most often. States’ rights is most often put forward as the cause of secession with Lincoln’s election, economic and cultural factors, and the settlement of the west also earning some votes. Scholars and historians may but forward a (mostly) unified answer that slavery was the cause of secession, but the public will not. And Civil War sites have to find ways to work through this divide, because no matter what you interpret at your site or how visitors will always ask the question: “What caused the Civil War?”

Those of us that have worked at a Civil War site know that that question is not always a simple one to answer and that there are multiple ways it can be asked. There are those visitors who ask it as a test. They are seeing if the staff member answers the question correctly so they can then ask more questions or, if unsatisfied, move onto someone else who is “smarter” or “better informed.” There are those who direct it as a challenge. They want to argue with someone to make their point heard, so they are gearing up in their heads while you make your answer so they can correct you and make you see the “truth.” And then there are those visitors who simply are asking the question because they can’t remember, don’t know, or are confused about what they have heard. These visitors can sometimes be tough to handle, but the lesson learned is that as much as we historians want there to be one version of history, there never really will be. Everyone comes in the door with different knowledge, different traditions, different pre-conceived notions, and different educational backgrounds, and they come to a historical site for different reasons. Some will be willing to learn something new, some won’t. History IS essentially his-story; stories that are told and retold over time, changing over time and from place to place. Even the stories in our museums and sites change; it’s called changes in interpretation. It is like classic fairy tales; the story is the same and recognizable in all its renditions, but details change in different cultures.

Of course, our job as historians and interpreters is to educate people about the full picture, about the stories we believe contain the full truth as we see it. Part of this is understanding where different theories about the causes of secession come from and having a good argument in place to talk to those visitors who are willing to listen and think about it. Part of it is encouraging people to “check their ancestors at the door” and be willing to be open minded as they visit your site or museum. Part of this is realizing (as most of us do) that this issue is still alive and able to flare passions; sometimes you cannot win. And part of it is realizing that the stories and backgrounds that these visitors bring with them is just as much history and part of our stories as the information contained in our tours and exhibits. Perhaps history should be shared instead of just taught. Listen to them and maybe they will listen to us. Yes, secession is all about slavery, and each of the other answers commonly given all point back to slavery, but not everyone believes that. Finding out why just might be the more rewarding experience than proving to a visitor that you know what you are talking about.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.