"Yankee Candy Would Choke Me": Fredericksburg Occupied!!

/The location of the city of Fredericksburg meant that it would be a crossroads for the Union and Confederate armies. At the beginning of the war, Confederates came through town on their way to the front or to garrison the area. Due to the ravages of disease in the army, Fredericksburg became a town of hospitals, and suffered a Scarlet Fever epidemic that killed as many as 150 children.

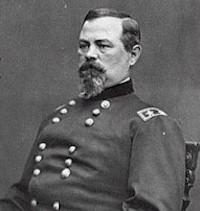

On April 18, 1862 it was the Union army that came into Fredericksburg. That Good Friday morning the Confederates left town, burning the bridges over the Rappahannock River, making way for the Federals to arrive that afternoon. Mayor Montgomery Slaughter and a delegation from the town surrendered Fredericksburg on April 19 under the agreement that local citizens and private property would not be harmed. Union soldiers under General Irvin McDowell built bridges, crossed on May 2, and settled on the outskirts of town for a four month stay.

McDowell held his men under strict discipline to leave private property alone, and punished soldiers caught bothering civilians. Betty Herndon Maury wrote on May 22, 1862: “Two soldiers are now tied back to back to a tree in front of the court house with a board over their leads on which is written, ‘For entering private houses without orders.’” There was little damage done to the town that summer, and Fredericksburg residents had to concede that the soldiers were largely well behaved. The only real damage to property was the exodus of slaves seeking their freedom in the Union lines. Suddenly, women were forced to perform tasks they were not used to, and those whose slaves remained were constantly on alert for signs their loyalty was straying.

But well-behaved or not, the women of Fredericksburg made it clear that they were unhappy with the Yankee invasion. They fussed over the interrupted supply and mail lines as well as the rules and curfews set by the Federals. Sometimes it was the silent treatment, a look, a turn of the nose. Oftentimes women refused to walk under the United States flag until it became almost a game of the Union soldiers to trap them into coming in contact with it, but the women remained resolute:

Becky Lewis went around one of their flags a few days since, and as soon as she past, some officers made a boy take a union flag, and run after her and shake it over her head. On Main Street there lives an Irish or Dutch woman who keeps boarding house. A lady passing by one day walked out in the street instead of going under the "Stars & Stripes" when this woman commenced making remarks about her to an officer standing in the door; and among other things said there was no use going out in the dirty street. The lady quietly turned round and said "Southern dust preferable to Northern rags.” (Lizzie Alsop, July 14, 1862)

Southern women did not always react silently (or politely) to Union soldiers. Spitting was common as was throwing waste out windows on soldiers below. One women even told a Union soldier to kiss her backside in one of the downtown streets. Even children got in on the action. Betty Maury wrote proudly of her daughter:

Nannie Belle was playing on the pavement yesterday evening when a soldier accosted her and asked her if she would not go down the street with him and let him buy her some candy. She replied, “No, thank you; Yankee candy would choke me!” He seemed much amused.

At the end of the summer, new commander General John Pope changed the policy towards civilians. He wanted oaths of allegiance for citizens, allowed soldiers to seize provisions, and required citizens to repair guerrilla damage. In response to the arrest of seven Unionist citizens, 19 prominent Confederate sympathizers were arrested and sent to Washington (they were released in September). By this point, however, Fredericksburg had lost its importance for both armies, the fight was headed elsewhere.

On September 1, 1862 the Union army burnt their bridges and left the city of Fredericksburg, and its relieved citizens. Reflecting upon the town and its inhabitants, Union General John Gibbon said, “Poor creatures they have seen but little of the horrors of war…If they ever do see really what War is, they will sigh for the times they are now passing through.” Fredericksburg had not truly suffered during their summer occupation, but they would in the future. The armies would be back again.

Suggested Reading

Blair, William A. “Barbarians at Fredericksburg’s Gate” The Impact of the Union Army on Civilians.” In The Fredericksburg Campaign: Decisions on the Rappahannock. Edited by Gary Gallagher. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Felder, Paula, and Barbara Willis, eds. The Journal of Jane Howison Beale of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Fredericksburg, 1979.

Hennessy, John. “For All Anguish, For Some Freedom: Fredericksburg in the War.” Blue and Gray(Winter 2005).

O’Reilly, Francis Augustín. The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Rable, George. Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.