Righteous or Riotous? The 2nd Ohio Cavalry and The Crisis

/This post is the latest in Zac Cowsert’s series “The Civil War in the Press,” which explores the interactions between soldiers and civilians, politics and the press throughout the Civil War. You can read other posts in the series here.

As the snow fell from a wintry sky on March 5, 1863, over a hundred men gathered on the fields of Camp Chase, outside Columbus, Ohio, ostensibly for the purposes of attending church. For a “church party,” however, they were oddly equipped, armed with “clubs, hatchets, and axes.” Once the men—soldiers of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry—had assembled at their “appointed rendezvous,” they formed up into a line and made their way onto Columbus. The soldiers had been planning this foray for some time, knowing that Sunday church offered them the perfect excuse to enter town and commence their mischief.

On the outskirts of the city, the men approached the Broad Street Bridge, a long wooden structure guarded by a sentry.

“Halt, who comes here?” the sentry cried.

“A party to church,” Sergeant Harris of Company E confidently replied. The confident air did the trick, and the men passed on into the heart of the city.

After winding through the city streets, someone declared, “This is the place.” The armed party came to a halt at the corner of Gay Street. Sergeant Harris posted two men on each corner to keep watch. With lookouts properly posted, the men of the 2nd Ohio put their clubs, hatchets, and axes to use and “poured into the building,” intent on destroying the offices of the newspaper The Crisis.

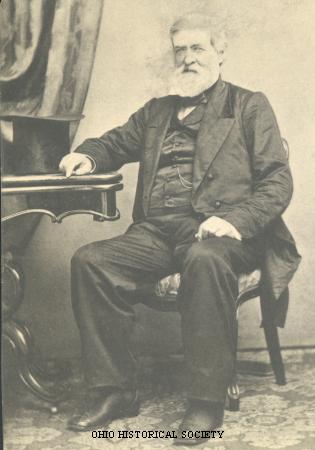

The Crisis was an incendiary, eight-page Democratic weekly newspaper published in Columbus. The paper was the product of sixty-year old Samuel Medary, a longtime veteran of Ohio Democratic politics. Medary launched the paper in 1861 in hopes of staving off war, determined that he “should not be a silent spectator of the most dangerous controversy that every impended over the American people.” Medary felt that abolitionists and "Black Republicans" had dragged the nation into war by violating Southerners' rights, and he deeply opposed the Union war effort.

As the war dragged on, Medary used The Crisis to lambaste the Union army and the Republican party, and the feisty editor charged that attacks on the Democratic press were attacks on free speech. Little did Medary know that his very own paper would soon be under attack from the very forces he so often critiqued.

Union soldiers did not take kindly to Medary’s Copperhead rhetoric. William Smith called it “the hottest Rebel sheet to be found in the Country, either North or South.” Isaac Gause recalled that when the Second was serving in Kansas, the Crisis published a speech by Clement Vallandigham, “in which he expressed the wish that no soldier that crossed the Mason and Dixon’s line would live to return,” a sentiment not forgotten by the Second when they returned to Ohio in 1863. Perhaps Henry Whipple Chester said it best by stating, “The Second Ohio boys had imbibed too much of the free air of Kansas not to notice such fragrant disloyalty.”

And so on March 5, 1863, men from the 2nd Ohio went into Columbus and wrecked The Crisis’ offices. Windows were smashed, and the Ohio soldiers tossed furniture, books, and papers out onto the streets. The soldiers began dumping office goods into the Sciota River. The ransacking quickly drew the attention of several policemen, who were intercepted by the lookouts Sergeant Harris posted and warned not to interfere in the soldiers' business. Soon enough the office was thoroughly trashed, and the rowdy Ohioans began their return to camp.

At this point, one of the soldiers informed Sergeant Harris that despite the destruction, the newspaper’s print-type had not been found. The sergeant, determined to destroy the type and thereby hinder The Crisis’ publication, decided to turn back into the city and head towards the steam printing press in hopes of finding the type there. Isaac Gause suggested that sending “men enough to the bridge to hold it, as it was our only means of escape.” So the Ohioans split up; many went ahead to the bridge, while Sergeant Harris led thirty men back into Columbus to pay a visit to the printing press.

Unfortunately for Sergeant Harris, the type was not located at the printing press either. No one was sure just where The Crisis was actually printed. Stumped, the Ohioans headed back to bridge to reunite with their comrades. The hundred vigilantes marched “in perfect order” past the “patrol, guards, police, and many others…going in the direction of the Crisis office.” Once again claiming to be a “church party,” the men of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry returned safely and scot-free back to Camp Chase.

Over the next few days, efforts were made to find and punish the responsible parties. No one was ever found guilty, although searches of the barracks forced many of the vigilante soldiers to burn the trophies they brought back with them. Henry Chester recalled that the “big stove used to warm the barracks was kept going nearly all night burning the papers and books and all incriminating evidence.”

While the Ohio troopers may have hoped to send Medary a message, in reality they simply provided him with more ammunition. When Medary returned to Columbus on March 6, the day after the attack, he received a hero’s welcome. A crowd met him at the railroad station, he was carried on shoulders to his carriage, and a brass band trumpeted his return. On March 7, The Crisis crowed about the attack on its offices and on free speech. “To the soldiers who participated in last night’s outrages and violence, I have to say, your conduct is strangely inconsistent with your duty, and the holy purpose for which your country put arms in your hands,” Medary declared. “Your mission is to uphold the laws, not to violate them…Forgetting your duties as soldiers, you have become rioters and buglers; and instead of being, as you ought to be, the protectors of the rights of citizens, you have become their assailants…”

The attack on The Crisis underscores the conflicting definitions of loyalty that can plague a nation during times of war. For the soldiers of the 2nd Ohio, they envisioned themselves as righteous patriots when they marched through downtown Columbus to sack The Crisis. As Samuel Trescott wrote home of the incident: “It was a secesh paper and aided the rebels and as such should be put down.” Even in their memoirs, most of the troopers look back on the sacking of The Crisis with a light-hearted, approving air.

Samuel Medary, on the other hand, believed (rightly so) that he had every right to criticize the government, the army, and whoever he might choose. However repugnant his views may have been to Union soldiers, their dissent did not give them license to "become rioters and buglers." And as a seasoned politician, he utilized the attack to his advantage, drumming up Democratic support for his paper and his claims that the Democratic free press was under siege.

These contradictory definitions of loyalty and patriotism shaped the war on the home front and could produce moments of vigilantism and violence, as happened on March 5, 1863 in Columbus. Such incidents only spurred further public discussions over loyalty, patriotism, and the course of the war. Thus, the actions of the 2nd Ohio were defined in the eye of the beholder, as either righteous or riotous.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Further Reading and Sources

Chester, H.W. Recollections of the War of the Rebellion. Wheaton, IL: Wheaton History Center, 1996.

Dee, Christine. Ohio's War: The Civil War in Documents. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2006.

Gause, Isaac. Four Years with Five Armies. New York & Washington: Neale Publishing Co., 1908.

Harper, Robert S. "The Ohio Press in the Civil War." Ohio Civil War Centennial Commission. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Risley, Ford. Civil War Journalism. Denver, CO: Praeger, 2012.

Roseboom, Eugune H. "The Mobbing of the Crisis." Ohio History 59, no. 2 (April, 1950): 150-153.

"Samuel Medary." Ohio History Central.

Smith, Reed W. "The Paradox of Samuel Medary, Copperhead Newspaper Publisher," in The Civil War in the Press. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2000.

Tenney, Luman Harris. The War Diary of Luman Harris Tenney, 1861-1865. Cleveland, OH: Evangelical Publishing House, 1914.