18,000: A Comparison of May 3, 1863 and May 12, 1864

/On the morning of May 3, 1863, Confederate soldiers slunk through the thick foliage that dominated the Wilderness around the Orange Turnpike and the tiny hamlet of Chancellorsville, Virginia. Around 5:30am, Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, outnumbered, outgunned, and divided, unleashed a series of brutal frontal assaults on the Union positions around the Chancellor House. By the late morning, over a span of five hours, the Confederates had battered and broken the will of Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac, compelling him to abandon the intersection near Chancellorsville and retreat back towards the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers.

A little over a year later, in the early morning hours of May 12, 1864, though a grey mist and damp fog, twenty-thousand Union soldiers of the Union Army of the Potomac, led by Ulysses Grant, charged towards the earthworks constructed by the Army of Northern Virginia near Spotsylvania Court House. Over the next twenty-two hours, until the early morning of May 13, Union and Confederate soldiers proceeded to engage in hand-to-hand fighting, battling in and around earthworks known today as the Bloody Angle. Blood, rain, and muck mixed together as soldiers from both sides struggled to drive their opponents back. A twenty-two inch oak tree near the Confederate earthworks, riddled by rifle fire, splintered and fell onto Confederate soldiers as the battle raged.

Aside from the geographic proximity—roughly twelve miles—a common element links these two battles. As a tour guide at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park this past summer, I gave tours on a weekly basis at both the Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania Court House battlefields. As part of my tours at both sites, I attempted to intertwine the narratives of these two engagements through one simple number: 18,000. At both Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania Court House, the Union and Confederate forces suffered approximately 18,000 casualties on the two specific days mentioned above. Yet there exists a staggering difference in regards to the type and duration of the fighting witnessed by Union and Confederate soldiers on May 3, 1863 and May 12, 1864. In five hours of fighting on the morning of May 3 at Chancellorsville, Union and Confederate soldiers suffered 18,000 men killed or wounded. To put that in perspective, an exhibit at the Chancellorsville Visitor Center provides a digital clock that simulates those five hours and the casualties experienced that morning. 18,000 casualties constitutes one casualty every second for five hours. Imagine watching a regular clock. Every time the second hand ticked by, for five hours, that equaled a Union or Confederate soldier that became a casualty. One year later at Spotsylvania, the fighting in the earthworks exacted a nearly similar toll on May 12/13, 1864, but over a much longer duration. The fighting that morning lasted for nearly twenty-two hours as another roughly 18,000 men became casualties of war. While less compacted than the battle at Chancellorsville, the fighting in earthworks throughout May 12 and 13, witnessed the onset of extremely brutal, close quarter fighting that dominated the remainder of the war.

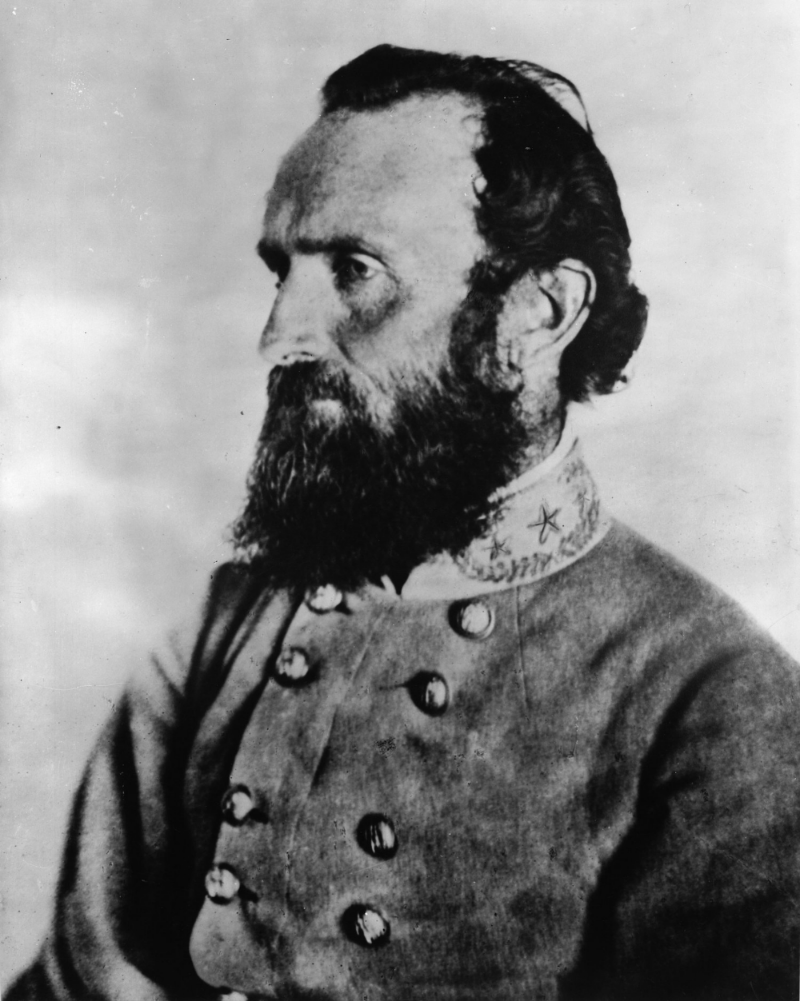

I attempted to connect these two separate battles on my tours because, despite their lethal similarity, historians and buffs alike tend to neglect one of these two days. I have no statistical evidence to prove this, but I would wager a fair amount of my mediocre graduate student salary on the fact that most Civil War enthusiasts would point to the Bloody Angle as a more deadly engagement than the fighting on May 3 at Chancellorsville. Why? The answer, I believe, lies in two separate parts. The first has to do with the mortal wounding of Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville, as well as the marked difference in the fighting witnessed in 1864, as compared to earlier in the war.

Few individuals capture the attention of Civil War enthusiasts and academics as much as the pious, eccentric, and martial Jackson has been able to do. His wartime experiences dominate countless books, blog posts, and academic careers. The Chancellorsville Visitor Center sits near the spot where Jackson’s own soldiers mortally wounded him. It makes sense then that the guided tour would focus on the story of May 2, Jackson’s flank attack, and his subsequent, ill-fated reconnaissance. Without a doubt, Jackson’s untimely passing was a significant blow for Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. Yet his death has become the defining feature of the entire Chancellorsville Campaign. This attention to Jackson makes sense, many of us are drawn to study the Civil War because of specific individuals and their experiences. It is the best way for us to connect with the conflict. Mortality plays a key part in the equation as well. No single individual’s death in the war is better documented than Jackson’s final days. As a result, his death offers the perfect opportunity to connect with the massive loss of life on a personal scale. Therefore, Jackson’s popularity, both when he was alive and over 150 years since he passed, overshadows most of what happened after the evening of May 2, 1862. In particular, it obscures what happened on the next day, the point of the battle that truly determined Lee’s success and presented him with what is arguably the most unlikely of his many victories.

The second reason deals primarily with the sheer brutality and duration of the hand-to-hand combat at Spotsylvania Court House. For over twenty rain-soaked hours, Union and Confederate forces slogged it out in the trenches of the Muleshoe Salient. The Overland Campaign in the late spring and early summer of 1864 was a radical change in the conduct of the war in the eastern theater. Grant’s actions at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor signified an unrelenting warfare that would eventually help exhaust the Confederacy. The Bloody Angle consequently offers up the perfect opportunity to display what the last year of warfare would come to look like for Union and Confederate soldiers. Trenches, increasing death tolls, and constant contact, all came to define the war in its closing months. Spotsylvania demonstrates that in all its mud and blood-soaked brutality. The prolonged, fortified nature of the fighting at the Bloody Angle allows us to remember the Angle as especially lethal, when in fact almost the same amount of casualties had been incurred in far less time two years prior, twelve miles away.

The wounding of one man and a radically different style of warfare overshadows the lethal connection between these two battles. At Chancellorsville, the story of Jackson’s death makes the battle seem so personal, while the bitter fighting at Spotsylvania, where dead and wounded men disappeared into the mud-soaked ground and fog-laden surroundings, makes the war seem so impersonal. My key point, when I gave tours of both battlefields and in this post, is that both battles produced the same amount of casualties. Although the style of fighting was vastly different at Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania Court House, we remember one as more brutal than the other. The truth though, is that this is how we remember these two specific days and that a similar level of brutality existed through both engagements and throughout much of the entire war.

Chuck Welsko is currently a doctoral student in 19th-century American history at West Virginia University, where he also received his master’s degree. An alum of Moravian College in Pennsylvania, he has also worked for local museums and interned with the National Park Service. Chuck’s research focuses on the mid-Atlantic region, in particular the intersection between politics, rhetoric, and the conceptualizations of loyalty during the Civil War Era. ©

Sources and Further Reading:

Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville (Boston: Mariner Books, 1996).

Rhea, Gordon C. The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern, May 7-12, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005).

*In addition to the battlefields of Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania, Fredericksburg-Spotsylvania National Military Park contains the Fredericksburg and Wilderness battlefields.