"Still on Parade:" Civil War Veterans and Civic Expression in Memorial Day Parades

/“Each member of this little band of survivors of a war that is part of a vanished era has seen a whole lifespan of seventy years pass since his last battle was fought... Children unborn when they enlisted in Lincoln’s time have died of old age, while they march on.”

- “20 G.A.R. Men, Still ‘on Parade,’ Get Ovation in Memorial March,” New York Times, May 31, 1934.

In terms of civic expressions of patriotism, few ceremonies are more quintessential than the Memorial Day Parade. Although the holiday honors those who fell in the service of the nation, veterans have always had a pivotal role in public expressions and observances. Veterans of the Civil War continued to participate in Memorial Day Parades well into the twentieth century, but as the years waned on, their role in these exercises began to change. By the 1930s, Civil War veterans were largely viewed by the public as curiosities or living memorials, their experience a lesson that Americans could draw upon for modern issues.

As the decade of the 1930s dawned, the influence veterans held over commemoration waned drastically. Aging bodies and dwindling numbers became the veterans’ defining characteristic in the public eye. Their steps were described as “feeble” and “faltering,” their “bent and hobbling” figures struggled to walk a few blocks in a parade. Their experiences in both the 1860s and 1930s were oversimplified with blanket statements such as “they were old men yesterday, crippled by battle or by age, some half-blind, many deaf, but all proud of the past and happy in the present.”

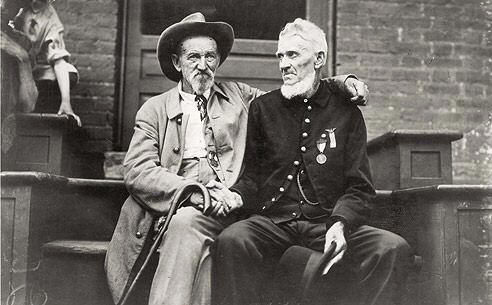

Confederate and Union veterans at Gettysburg in 1938

Temporal distance from the war itself allowed for the veteran’s wartime experience to be portrayed as not only superficially heroic, but something with which the aging warriors were prideful and content. The remaining living veterans were also seen as representing and memorializing those already lost, either to the war or to the seven intervening decades. This element of sacrifice became key to how Americans viewed the Civil War in the 1930s, as an event of just suffering that united the nation.

At this time, the media seems to have an almost-obsession with quantifying the remaining Civil War veterans. Estimated numbers such as “dozens” are never used to describe groups of veterans; instead, exact figures are almost always included. For example, when tracking the Grand Army of the Republic’s participation in New York City’s Memorial Day exercises throughout the decade, the rapid thinning of the ranks can be traced. The veterans who were able to walk in the parade numbered thirty-two in 1932, twenty in 1934, and only ten by 1939. Age was also quantified. Exact years were always used when describing individual octo- and nonagenarians, and even groups were described in precise manners such as “the youngest was 86 and the eldest 95. The total of their ages is 1,797 years.” Conversely, the small number of veterans allowed for common soldiers’ stories to easily be told. Although personal information was usually relegated to the veterans’ wartime experiences, the absence of still-living generals and officers allowed the heroism and sacrifice extolled by 1930s Americans to be that of the rank and file. For example, the “hobbled” figure of Robert Cain, “an aged Negro, one-time powder monkey under Farragut at New Orleans and Mobile Bay” who lost an eye during the war was mentioned in no less than three articles covering parades in three different years.

Civil War veterans were nearly always presented as figures from another era, even uncomfortable in modern times. When veterans were reunited, they created their own historical space. “And so the veterans of Vicksburg and of the Wilderness came into their own once more, came back to the world of living events from their days of dreaming of the glories of the past.” Again, age is emphasized to the extreme, in some cases by the veterans themselves. Frank Hanley, 88 in 1933, attended the parades every year with the purpose of ensuring his surviving comrades he was still alive, stating, “I’m an old fellow, and lots of people think I’m dead…I may be dead in a couple of days, but I want ‘em to know I’m alive now.”

Memorial Day exercises were an avenue through which veterans in general were consistently in the public eye, and this resulted in numerous comparisons with the younger veterans of other wars. Statements such as “the tap of canes and the gentle creak of crutches kept pathetic time to the blare of marching tunes and the clank of arms yesterday as the old and the disabled, veterans of Gettysburg and Bellau Wood,” compared the ravages of age to the destructive horror of America’s most recent war, in which North and South fought together. Age and disability were seen, together, as factors that separated these veterans from modern society, at least during these public expressions of patriotism.

The juxtaposition of the old veterans with current military units was also seen as a warning. The conflict between north and south was by far America’s most destructive war, in terms of both impact on the country’s landscape and the loss of human life. But in these civic expressions, the overt destructiveness of the Civil War was underemphasized, and instead focus was once again placed on the heroism and just sacrifice of the boys in blue and gray, especially when compared to the perceived futility of modern war. Statements such as “many units of the New York National Guard in field service uniforms gave the parade a grim hint of what modern day war might mean,” grew in frequency as the decade drew to a close and tensions in Europe and Asia began to boil over. From “towns and hamlets throughout America there came fresh pledges…that the sacrifices made by those who gave their lives for their county should not be in vain.” The still-living veterans became part of a usable past for a patriotic nation fearful of a new-armed conflict. Americans in the 1930s were looking to the past as assurance not only for their present struggles at the height of the Great Depression, but also looking toward an uncertain future.

All too soon, America would enter that feared modern war. The number of Civil War veterans would continue to dwindle until they disappeared, with the last verified Civil War soldier dying in 1956. Men who had stormed the beaches of Normandy and Iwo Jima replaced them in the ranks of Memorial Day parades. And it is those men who decades later continue to march today. How do Americans in 2016 view them?

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, received her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. History and Public History from West Virginia University. She is an historian at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, and is continuing her education by pursuing her PhD, also at WVU. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments.

Sources and Further Reading:

“20 G.A.R. Men, Still ‘on Parade,’ Get Ovation in Memorial March,” New York Times, May 31, 1934. Proquest Historical Newspapers: Accessed January 18, 2015.

“21 of G.A.R. March Valiantly in Rain in Tribute to Dead,” New York Times, May 31, 1933. ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Accessed January 18, 2015.

“Nation’s War Dead Hailed in Services Here and Abroad, New York Times, May 31, 2015 ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Accessed January 18, 2015.

“Thin Ranks of G.A.R. Cling to their Place in Memorial Parade,” New York Times, May 31, 1932. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Acceessed January 18, 2015