Calls to Arms: "The" Confederate Flag in American Culture

/When asked why the American Civil War still holds such power over the American imagination, author Shelby Foote once observed, “because it’s the big one. It measures what we are, good and bad. If you look at American history as the life span of a man, the Civil War represents the great trauma of our adolescence.” More recently, at the 150th anniversary of the surrender at Appomattox, historian David Blight reflected, “The Civil War is a place we go to ask who we are and what are we becoming…it is our oracle.” The debates that tore the nation apart for four bloody years are eternal questions of the American condition, Blight explained. It is no small wonder then that the symbols of those conflicts remain contested as well, suspended in our national consciousness without a singular definition that holds true over time.

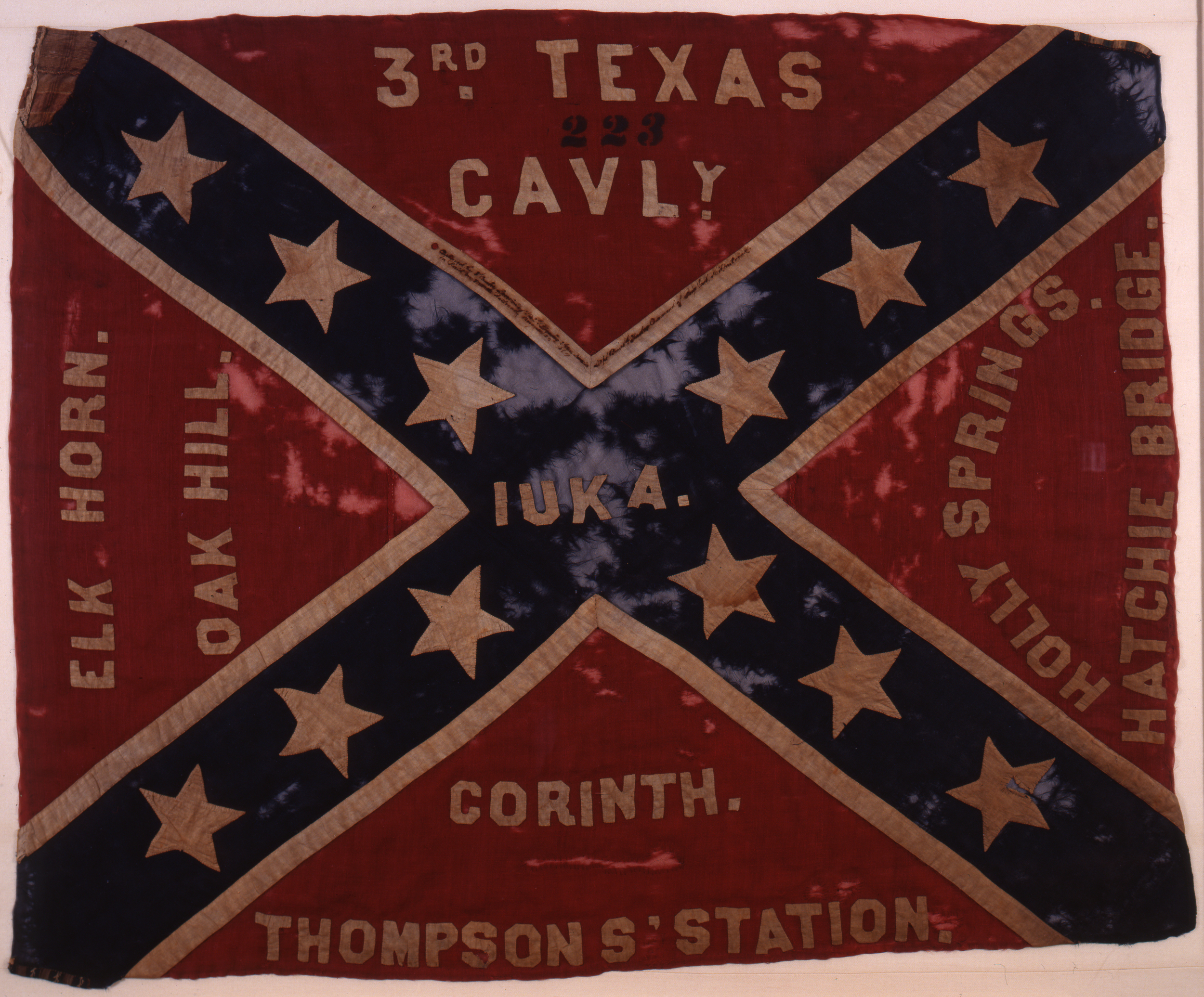

A variety of visual images remain from the war: the wrenching photographs of the fallen on the battlefield, their graves that dot the nation, the hallowed battlefields today. Yet perhaps the most recognizable image of the war, and undoubtedly one of the common, is that of the “Rebel flag.” This banner of the Confederate armies now adorns everything from beach towels, to truck beds, to boxer shorts, and stone monuments. Until recently, the flag remained within the margins of national news, making appearances every once and awhile when students were sent home for wearing Confederate flag shirts to school. One might walk past a lighter at the gas station or see license plate with the flag without thinking twice about the broader message relayed by those iconic stripes. Yet the actions of a single individual have thrown the use of the Confederate battle flag into the arena of public opinion, prompting even the chair of NASCAR to hope for its disappearance from public events.

Since the guns fell silent in 1865, the Confederate battle flag has been used in innumerable ways, suggesting that it has not nor will it ever have a single meaning. Rather, its ability to offend, and the meanings consequently associated with it, are perpetually tied to the contexts in which it is used and interpreted.

Contrary to popular belief, even the Confederates themselves had trouble agreeing on how best to represent their nascent nation. The original national flag, known as the “Stars and Bars,” looked remarkably like the United States flag – so much so that soldiers could not tell them apart on the battlefield. This similarity was intentional, however, as the Confederates sought to create a visual tie between themselves and the legacies of 1776, believing that they were the true inheritors of the Revolution. Through the repetition of imagery from the United States’ flag – including a field of blue with white stars and horizontal red and white stripes – Confederate politicians hoped to infuse their new symbol with meaning. As the war progressed, this tie became increasingly tenuous and the Confederate government radically altered their national flag to incorporate the symbol of its successful armies: the St. Andrews Cross.

This slow adoption of the "Southern Cross" during the first three years of war speaks volumes about the evolution of Confederate identity. A cursory glance at various states’ ordinances of secession reveals that states like Virginia and South Carolina saw very different meanings in the war and their choice to leave the Union. As a result, there was a definite divide between the act of secession and individual understandings of the principles for which the Confederacy stood. Unlike fire-eating states like South Carolina, Upper South states like Virginia left the Union reluctantly, hoping for reunion rather than war. With such divisions between states within this war-born nation, it is unsurprising that a battle flag would supersede a national flag in commanding loyalty and sacrifice. The Southern Cross accomplished what a government’s flag never could: uniting a divided people under principles upon which they could agree, without having to bridge the disjuncture between competing ideologies of national identity.

Despite its rather slow development as a national symbol, the Confederate battle flag became the most enduring symbol of the Confederacy at large when the war ended. It did not attest to consensus or a singular ideology, but rather of its power as an image to evoke emotion without making a particular, agreed upon claim. Baptized by the fire of war, the battle flag spoke not of meaning, but of a people, and thus continues to wield a contradictory and contested power that, like people, can never be one-dimensionally understood.

Relatively invisible in the years immediately following the Civil War, the Confederate flag made appearances almost exclusively at memorial events. This reality reflected the broader national trend to focus on the shared sacrifice of soldiers on both sides rather than debate the meanings and legacies of the war itself. After 1940, however, this began to change as the flag escaped its visual limitations and invaded popular culture. Initially the flag’s use remained fairly tame, making appearances at college football games, but more malignant forces like the Ku Klux Klan and Dixiecrat parties soon laid claim to the flag. Well into the 20th century, the flag took a prominent role in anti-Civil Rights movements and explicitly racist organizations. Yet simultaneously it found a place in popular culture, divorced from its historical legacy and showing up in television shows, band t-shirts, and tourist shop paraphernalia.

This dual trend continues today.

Walk into a shop in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and you can find Confederate flag-clad boxer shorts and license plates. In fact, it does not take proximity to a Civil War site to encourage the proliferation of Confederate flag kitsch. It is impossible to walk more than ten yards in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, an exceptionally popular vacation town, without spotting a Confederate bikini, t-shirt, or belt buckle.

Undoubtedly, the Southern Cross, is a potentially provocative image. But its proliferation in such a variety of spaces demands that it be viewed with caution. Art historian W.J.T. Mitchell has noted, offending images are, “radically unstable entities whose capacity for harm depends on complex social contexts. . . the offensive character of an image is not written in stone but arises out of social interaction between a specific thing and communities that may themselves have varied and divided responses to the object." Simply put, offending images are not inherently endowed with meaning. Meaning depends entirely on the context in which they are used and received by the viewer.

In many ways, this reality indicates that the flag remains useful for the same reasons it was useful in 1861. It has the ability to unite, divide, and confound people whether they agree about its meaning or not. More to the point, it forces people to react, bringing all their individual concerns, beliefs, and ideologies together in a response that is rarely predetermined and most likely in flux depending on the particular circumstances of their encounter with it. In a way, it is powerful while at the same time completely powerless and passive; because it lacks a fixed meaning, it allows the viewer to impose whatever meaning they see fit upon it, handicapping its ability to communicate. This again suggests that rather than transmitting a particular ideology, the flag remains powerful because of this perception that it must be saying something. It insists that there is something to react to, independent of intentions.

There is no doubt that its most relevant use today by a disgruntled individual is despicable and unacceptable, but that does not mean that one speaks for all. Like the history of the Civil War itself, the flag’s meanings are contested because they exist simultaneously. I would argue that this is not a reason to silence the flag altogether, but an opportunity to start conversations about the multitude of legacies it speaks to and the ways in which America’s great trauma resonates into our present. To apply a singular meaning to the flag – positive or negative – is to shut down a conversation that needs to happen, and one that should continue as we question who we are and what we are becoming.

Becca Capobianco is an education technician at Great Smoky Mountains National Park and an adjunct faculty member at Germanna Community College.

Sources and Additional Reading:

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: the Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.

Bonner, Robert E.."Flag Culture and the Consolidation of Confederate Nationalism." The Journal of Southern History LXVIII, 2002: 293-332.

Coski, John M.. "The Battle Flag: A Brief History of America's Most Controversial Symbol." North & South 4, no. 7, 2001: 48-63.

Elkins, James. “Just Looking,” in The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing, New York, 1996.:17-45.

Horwitz, Tony. Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998.

Mitchell, W.J.T. “Offending Images,” in What Do Picture Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago, 2005: 125-144.

Prown, Jules David. “The Truth of Material Culture: History or Fiction?” in History from Things: Essays on Material Culture, ed. Steven Lubar and W. David Kingery. Washington, D.C. 1995: 1-19.