Reforming a Nation, Saving the Union: the Problem of “Fallen” Women in Antebellum U.S. Culture

/As we discussed in a previous post, the variability of a growing country in the years prior to the Civil War prompted reformers to look to a variety of new public institutions to ensure stability. The founding principles of these institutions, embodied in the penitentiary system, were anchored in a belief that people were inherently good and that those who had strayed from the path of decent behavior did so as a result of corruption in society, not within themselves. It followed that if removed from these negative influences, individuals would voluntarily choose to right their behavior and return to a life of honesty.

However, the complicated role that women played in nineteenth-century American culture meant that the case of female crime was more complicated, and that despite the fact that many women were vocal and influential members of reform movements, their counterparts guilty of committing crimes were often left outside of the reformative process. Yet women played a unique role in the breakdown of the systems of control enforced prior to the Civil War, and consequently were responsible for challenging the normative barriers that endeavored to keep them on the margins of public life.

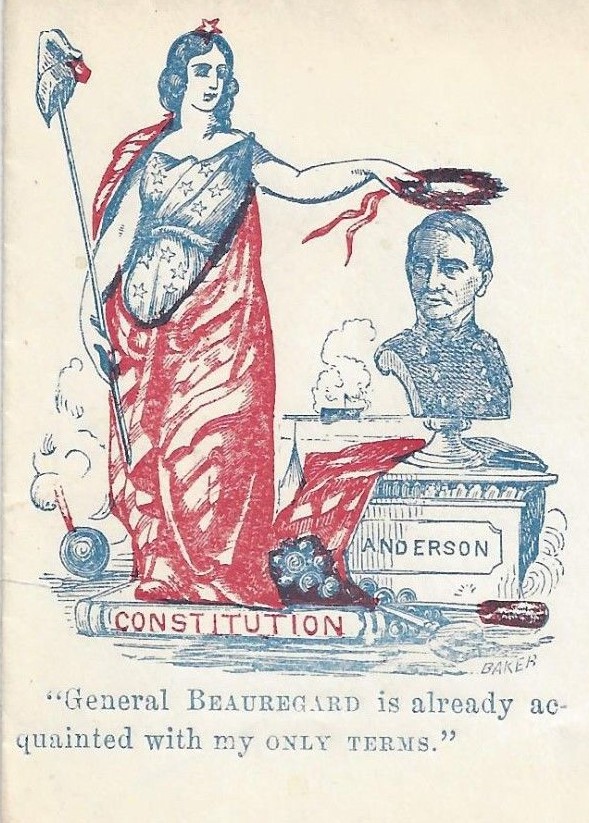

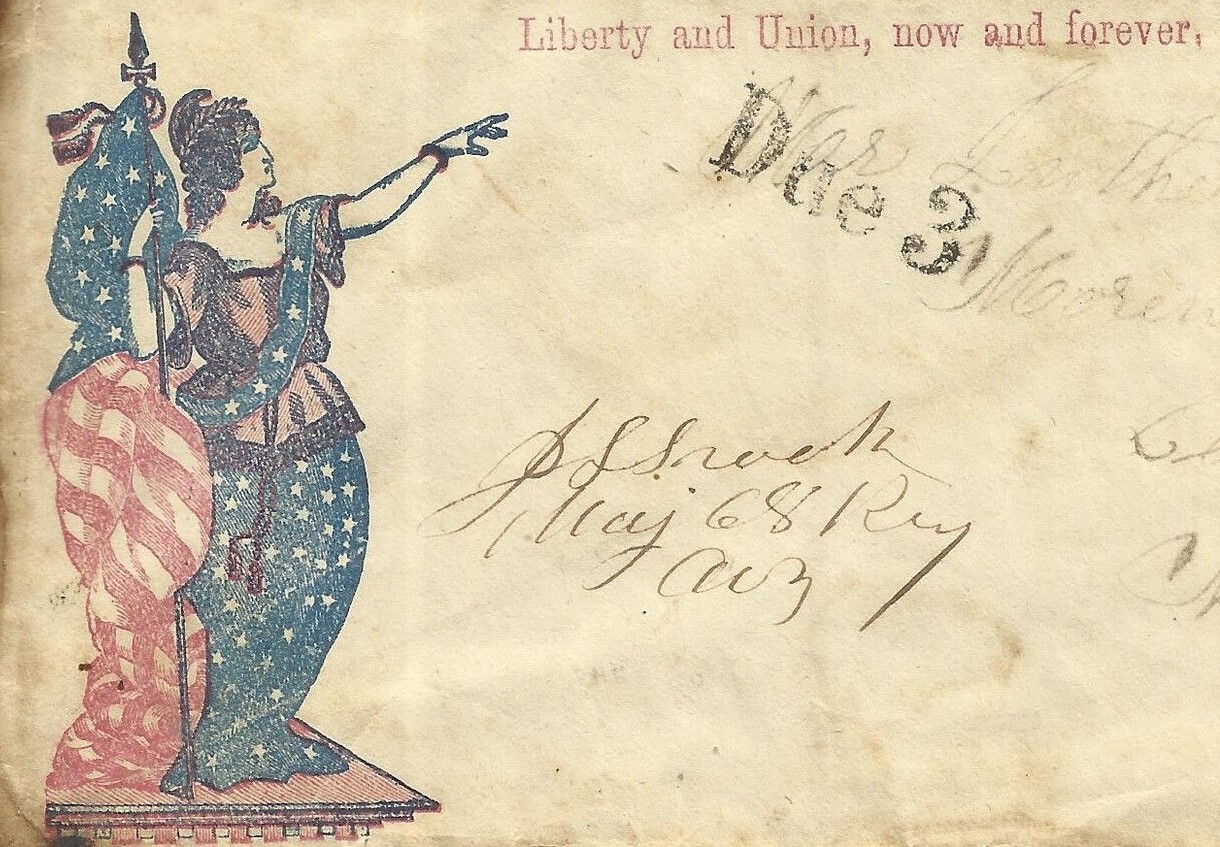

At the outbreak of the Civil War, soldiers marched off to war to defend liberty – always embodied in the form of a woman. This reality reflected a broader trend in antebellum culture that made women both symbols of the nation and the rocks upon which a healthy republic must be built. Americans expected women to be the stabilizing force in their homes by controlling the far more volatile whims of their husbands. It was the wife’s responsibility to control and channel their husband’s energies away from deviancy and towards the cultivation of self-control and virtue.

Likewise, a mother’s job was to raise republican sons to ensure the continued growth of a virtuous citizenry. These principles were a natural extension of the belief that women were morally and spiritually superior to men and that they could harness that superiority to positively influence the country. Prominent thinkers such as Catherine Beecher even went so far as to insist that women’s inherent domesticity and goodness could be a weapon with which to fight threats to American expansionism in the barbarous and unconquered areas of North America.

It should come as no surprise then that women were often left out of reform ideals and structures as, in theory at least, they were less likely to need them. Yet the reality of their absence was not that simple. Often disorderly women were not detained by police unless they were habitual offenders. Instead, their punishment and control remained in the hands of the men legally responsible for them. For the unfortunate female soul who did find herself in prison, the case was even bleaker as women were often neglected and abused within the walls of penitentiaries.

Again, this disregard for the well-being of female inmates was an extension of this same nineteenth-century belief in the natural moral superiority of women. If a woman had managed to fall far enough to land herself in prison, it followed that she had fallen much farther in her descent into the depths of depravity than her male counterparts. In the eyes of reformers, her cause was already lost. Though upstanding female members of society tried to remove this stigma and extend the possibility of restoration to women, they often met with resistance and ridicule from their male colleagues.

This conundrum was evident inside the nation’s first penitentiary at Cherry Hill, where despite the fact that women entered its gates almost immediately after its opening, a matron was not hired for their care until a scathing investigation revealed that corruption ran rampant as a result of the women’s neglect.

In 1835, just six years after Eastern State received its first prisoner, the Pennsylvania legislature ordered a review of the treatment of females within the structure that was supposed to serve as a social panacea. It became evident that rather than hire an official matron, the warden had employed the wife of an overseer, a one “Mrs. Blundin,” as an unofficial caretaker of the growing female population. Blundin herself was far from the upstanding woman reformers hoped to influence her fallen sisters, as she was accused of engaging in “licentious and immoral practices, indecent conversations, gross personal familiarities, and spreading a ‘filthy disease’” within the prison.

For their part, the female inmates in question, most notably a woman named Ann Hinson, fared little better. Other inmates testified that they had observed Hinson laid out drunk on the floor on numerous occasions, and that she had attended parties held by the warden in his personal quarters. Yet Hinson’s behavior was possible because her status as a woman, and the resulting assumptions about her inherent domesticity, required that she function outside of the prison’s normally strict structure of separate confinement. Hinson lived apart from her peers, residing in a cell block with men rather than women, because she was responsible for cooking for male inmates. Moreover, the warden’s clear neglect of her reformation enabled the behavior for which she was condemned.

A modern image of Cell Block 4, where Ann Hinson resided.

If individuals were truly good and simply corrupted by outside influences, as Eastern State’s founders insisted, then Hinson never had a chance to right her behavior. Instead, she was subjected to the same types of corrupting influences within the prison walls that had, theoretically, doomed her to a life of crime. Intent on righting this flaw, the state of Pennsylvania hired a matron to care for the female population at Eastern State in 1836. However, women still continued to function outside of the accepted boundaries of separate confinement.

As the nation grew, so too did the criminal population within Eastern State and consequently the number of incarcerated women increased. Though their place in nineteenth century society, imported into the prison’s walls, left them vulnerable to abuse and neglect, it also gave resourceful women an opportunity to more effectively undermine the rigid system in which they lived. In the midst of national chaos brought on by the advent of civil war, it would be a woman inside Cherry Hill who would play by far the most effective role in undermining the system and challenging the normative social expectations imposed by reformers.

Becca Capobianco received her M.A. in US and Public History from Villanova University. She has worked in education with the National Park Service and is an instructor of U.S. history at Germanna Community College. ©

Sources and Further Reading:

Bonner, James C. “The Georgia Penitentiary at Milledgeville 1817-1874.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 55 (1971): 303-328.

Carey, John H. "France Looks to Pennsylvania: The Eastern State Penitentiary as a Symbol ofReform." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 82 (1958): 186-203.

Dobash, Russell, R. Emerson Dobash, and Sue Gutteridge. The Imprisonment of Women. Oxford, UK: B. Blackwell, 1986.

Dodge, Mara. “The Most Degraded of their Sex, if not of Humanity: Female Prisoners at the Illinois State Penitentiary at Joliet, 1859-1900.”Journal of Illinois History 2 (1999): 205- 226.

Dorsey, Bruce. Reforming Men and Women: Gender in the Antebellum City. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Freedman, Estelle B. Their Sisters' Keepers: Women's Prison Reform in America, 1830-1930. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981.

Freedman, Estelle. "Their Sisters' Keepers: An Historical Perspective on Female CorrectionalInstitutions in the United States: 1870-1900." Feminist Studies 2, no. 1 (1974): 77-95.

Hahn, Nicolas Fischer. “Female State Prisoners in Tennessee: 1831-1979.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly. no 39. (1980): 485-497.

Halttunen, Karen. Confidence Men and Painted Women: a Study of Middle-class Culture inAmerica, 1830-1870. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

Hayden, Erica Rhodes. “Plunged into a Vortex of Iniquity”: Female Criminality and Punishment in Pennsylvania, 1820-1860. Nashville: Vanderbilt University, 2013.

Patrick, Leslie. “Ann Hinson: A Little-Known Woman in the Country's Premier Prison, Eastern State Penitentiary, 1831." Pennsylvania History 67 (2000): 361-375. www.jstor.org (accessed November 7, 2012).

Scheffler, Judith. “Wise as serpents and harmless as doves:” The Contributions of the Female Prison Association of Friends in Philadelphia, 1823-1870. Pennsylvania History: a Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 81 (2014): 300-341.