Patriotism in Print: The American Union, A Soldier's Wartime Paper

/This post is the latest in Zac Cowsert’s series “The Civil War in the Press,” which explores the interactions between soldiers and civilians, politics and the press throughout the Civil War. You can read other posts in the series here.

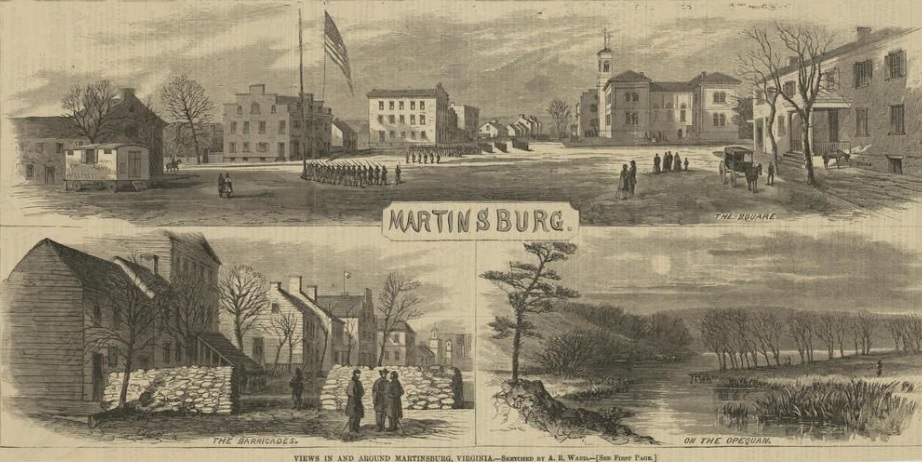

On the evening of July 3, 1861, a dozen Union soldiers (self -described “disciples of Faust”) broke into the offices of the of the Virginia Republican—a decidedly secessionist organ—and appropriated the newspaper’s office for their own use. The next morning—on the Fourth of July—the first issues of the American Union hit the streets of Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia). The newspaper—composed and printed entirely by Union soldiers—enjoyed a brief existence in Martinsburg, lasting only as long as the Union troops occupied the town. Despite its brief existence, however, the paper sheds light onto the patriotism and zeal of Union soldiers during the war's opening months.

The early summer of 1861 witnessed the sundering of the United States, as Southern states seceded and war loomed on the horizon. Armies of green troops, both Northern and Southern, mustered and march around the nation, and in western Virginia thousands of Union volunteers organized under the command of Major General Robert Patterson. Meant to occupy the attention of Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley, Patterson’s men secured western Maryland and occupied Martinsburg, Virginia.

Among this body of blue-clad troops marched Captain William B. Sipes of the 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Before the war, William Sipes served as the editor for the Pottsville [Pennsylvania] Register, a Democratic newspaper. Upon war’s outbreak, Sipes joined the 2nd Pennsylvania, a regiment whose three-month term of service reflected the widespread belief that the war would prove short and victorious. Despite the captain’s bars on his shoulders, however, William Sipes soon found himself in a familiar position, serving as editor for the American Union.

The American Union offered soldiers a glimpse into the wider world, particularly the military situation, around them. The army’s advance into Confederate Virginia received attention, as did the increasing destruction of property in the region: "The wanton and useless destruction of property in this region is so great as almost to baffle exaggeration." Such destruction, of course, further proved "the insane wickedness of the leaders of the Southern Rebellion." More mundane matters, such as announcements from high command, provost guard updates, and reports of nearby skirmishes kept soldiers abreast of the latest developments.

The American Union provided soldiers with a source of entertainment, as each issue contained a variety of songs and poems, often lauding Northern manliness or ridiculing the Southern war effort. Many of these literary pieces came from the hand of Private Samuel J. Vandersloot, 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry and “2nd Assistant” on the Union’s staff. A twenty-six year old lawyer from the quiet hamlet of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the young man clearly possessed a penchant for poetry and song. “Live on, live on, proud Union of the States, Our homage and prayers are thine own;” Vandersloot penned for the Union’s pages. “Every friend of freedom the moment awaits, When treachery y shall be o’erthrown.” Besides Vandersloot’s enthusiastic pieces, well-known literature—such as the Declaration of Independence and the “Star-Spangled Banner” made appearances.

The American Union’s staff, however, did not view Union soldiers at their sole audience. Each issues of the Union also contained addresses “To the People of Virginia,” which attempted to assuage the anxiety of Virginians and assure them that the blue-clad soldiers came as friends, not enemies. Arguing that the reasons for war had been “grossly misrepresented to you,” the Union asserted that Federal forces only meant to “reestablish peace and order” and uphold the Constitution. Hoping to end the South’s “unholy revolution,” the workers of the Union looked forward “to the time when the American Union will be reconstructed in all its grandeur and power."

The American Union lasted only a week. General Patterson’s troops soon left Martinsburg, leaving behind too the offices of the Virginia Republican from which the Union was produced. On July 21, Union and Confederate armies clashed on the banks of Bull Run Creek near Alexandria, Virginia. It was the war’s first major land battle, and it was a smashing Confederate success. The Rebels’ victory rested largely on reinforcement by thousands of Confederate soldiers from the Shenandoah Valley. The tremendous failure of General Patterson to pin down Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley helped confirm a Rebel victory at Bull Run and ensured that the war would last far longer than three months.

For Martinsburg, the departure of Union troops and their defeat at Bull Run allowed Confederates troops to reoccupy the city, and by October the Rebel Republican was once again in publication. The editor of the Republican, back in possession of a pulpit from which to preach, pilloried the “Hessians,” “thieves,” and “Federal hirelings” of the Union army who had printed the “diminutive” American Union and who had apparently “robbed and plundered the office” of the press upon their departure. Hoping for some justice, the Confederate editor published the names of those Union officers involved in the Union’s publication.

For the nation, however, the defeat at Bull Run ushered in the unhappy prospect of a long civil war. Tens of thousands of soldiers who had once enlisted for three months’ service now enlisted for three years’ service or the duration of the war. The 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry’s enlistment soon expired, leaving to each man to determine his next step. Samuel Vandersloot, the young poet and songwriter, went back home to Gettysburg and later became a clergyman—a fitting occupation for the young romantic. Capt. William B. Sipes, who had managed and edited the American Union, also went back home to Philadelphia, but instead helped raise the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry for Union service, a task he carried out “with the energy which characterized all his undertakings.” Sipes served through most of the war and was promoted several times, ending the war with a colonel’s bars on his shoulders.

With so much laying ahead of them, it seems likely that for many who helped produced the American Union, memories of its production would soon give way to the harsher reality of a long, protracted war. Yet throughout the Civil War, soldiers showed a penchant for creating spur of the moment newspapers. When Charleston, West Virginia fell to Confederate occupation in 1862, Rebel soldiers started up The Guerrilla. Texan soldiers fighting in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma) put together the Choctaw and Chickasaw Observer, of which at least some copies were written by hand. When Union troops entered Vicksburg, they went ahead and printed the local Rebel paper that was still on the press...with an addition announcing the fall of the city. These newspapers collectively suggest that soldiers North and South hungered for news, entertainment, and encouragement and were willing to create their own sources of news when times required.

A version of the article first appeared in the West Virginia and Regional History Center's blog. I'd like to thank the WVRHC for allowing me to reuse this article; the WVRHC contains a large archives of Civil War related materials, including copies of The American Union and The Guerrilla.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Sources & Further Reading:

American Union [Martinsburg, WV]. Chronicling America. Library of Congress.

Richmond Daily Dispatch, “Re-issue of the Martinsburg (Va.) Republican,” October 16, 1861.

Noyalas, J. A. "Martinsburg, Virginia, During the Civil War." Encyclopedia Virginia.

Prowell, George R. History of York County, Pennsylvania. Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1907.

-----. The Twentieth Century Bench and Bar of Pennsylvania. Chicago: H.C. Cooper, Jr., Bro. & Co., 1903.

Rafuse, Ethan S. A Single Grand Victory: The First Campaign and Battle of Manassas. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 2002.

Sipes, William B. The Seventh Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Cavalry. 1906. Reprint. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press, 2000.

Vale, Joseph G. Minty and the Cavalry. A History of Cavalry Campaigns in the Western Armies. Harrisburg, PA: Edwin K. Meyers, Printer & Binder, 1886.